Learning to read at an early age, the cognitive neuro-biologist and scholar of reading, Maryanne Wolf, immediately became an avid reader and as a grown-up studied literature. After completing her graduate studies she spent a year teaching English in Hawaii and suddenly realising how important reading was, began to think about reading as a process and how it works. Revising her whole life plan, she decided to move away from studying the content of words to focus instead on the science that underlies the process by which words evoke meaning in the mind of a reader. In proficient or what she calls “deep reading”, the empathy that a reader experiences with a narrator, a writer or a character enables the reader to experience whole new worlds of feeling and it was this process from a printed letter on the page to the activated and totally engaged mind of a reader that Wolf decided to set about investigating.

M. C. Escher, Reptiles

Examining the neurobiology of the reading process Wolf found that during reading, the speakers of different languages use the different parts of the brain that are involved in reading to varying extents. This reflects the fact that during processing, different languages place different demands on different parts of the brain. These results are based on comparisons between languages such as Chinese which are hieroglyphic and European languages which use alphabets. Wolf’s interest in what happens in the brain when we read, also led her to consider the complex phenomenon of dyslexia when, at the learning-to-read-stage, an inability is encountered and reading is learnt using other channels. As the experience of deep reading from a book and digital ways of assimilatring and processing information are differently represented in the brain, Wolf is deeply concerned that both literature and the culture of informed and considered reflective analysis which a critical, proactive understanding gives rise to, are being undermined by the superficial scanning and cherry-picking styles of reading which have become widespread due to ever more material being read on screens.

In a survey which compared the degree of comprehension arrived at when a work was read in printed form with the comprehension arrived at when the work was read in digital form, the results clearly indicated that a higher degree of comprehension was reached by people reading physical books. This was conducted by a team assembled around Anne Mangen at the University of Stvanger. Carried out over the years 2018 and 2019, the project correlated the results established in over 50 surveys and ultimately drew on 170,000 test persons. The inferior performance of people reading from screens is partly explainable as being due to the distractions that are usually activated whilst a text is read from a screen, such as e-mails, moving graphics and links that are embedded in the text. In addition the text on a screen is immaterial and cannot be haptically interacted with except through a mouse which is not the same thing. As beings with bodies we are used to experiences things with all our senses. In the case of reading from a physical book, this is our sitting quietly and the fact that the book is a material object with pages that we turn and which has a cover and pages with a designed character that we associate with the book. In turning pages we not only get a physical feel for the book as an object but also for the unfolding of a story or the development of an argument. In this context, as Wolf points out, the value of bedtime stories is immense. In a secure and reassuring environment, a child is introduced to the world of reading. The repeated experience of lying in bed or sitting on a parent’s lap and being read to sends invaluable emotional signals that are essential for the future development of an in-depth relationship to reading and the written word. Yet it is precisely this introduction to reading that is being skimped on through an overuse digital devices.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Librarian

For Wolf, although there is a growing and very real danger that instead of genuine democracy we may suddenly find ourselves living in sham in which democracy has been short-circuited through our failure to maintain a culture of deep reading and critical analysis, this does not mean that everything digital is bad. Rather, just as children are capable of growing up learning not just one but two languages, Wolf argues that we should do everything we can to ensure that our children are brought up in a way that results in them being able to jump between two different ways of reading and assimilating written material. The one is the traditional style of reading from printed books in a manner that in an adept reader results in the phenomenon of deep reading. The other is the internet style of rapidly processed quick analyses that allow us, from a wide range of data to form impressions without being overloaded or of becoming bogged down in endless detail. To this effect, in her most recent book, Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century, Wolf asks such questions as how does literacy change the human brain? What does it mean to be a literate or a non-literate person in today’s digital culture. What will be lost in the present reading brain and what will be gained through the use of mediums other than print? What are the consequences of a digital reading brain for the literary mind and indeed for writing itself? Can knowledge about the reading brain combined with advances in technology offer new forms of literacy and new forms of knowledge that will be available to peoples in remote regions who would otherwise not have the chance to become literate? In dealing with these questions, Wolf again draws from research in cognitive neuroscience, psycholinguistics, child development and education. Considering literary examples from world literature, her aim is to preserve the deepest forms of reading from the past, while developing the cognitive skills necessary for future generations. As the Children’s Literature Association Quarterly says:

“Essentially, the reader is here treated to two books in one – a thorough review of how deep reading and digital literacy are differently represented in the human brain, and a report on a global project to bring literacy to children (and adults) who, without mentors or teachers, would not have any other path to achieving it.”

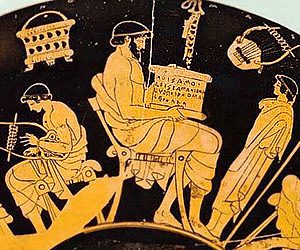

A reading machine from The Various and Ingenious Machines of Augostino Ramelli, 1588

The balanced offsetting of the pro’s and contra’s of digital culture in Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century, is countered by the more alarmed messages of Wolf’s previous two books. In Reader Come Home, The Reading Brain in a Digital World, she nine letters, each of which begins “Dear Reader”. In these letters she describes how the reading process works, differentiating between deep reading and skimming and cites alarming evidence on how, due to digital technology, the attention span of adults has decreased alarmingly. In cultures where deep reading and critical thought are absent, a unified, monotone culture arises. There being no pluarality of different points of view and only ever one approach to things, dogmas arise and the asking of questions becomes stifled:

“When language and thought atrophy, when complexity wanes and everything becomes more and more the same, we run great risks in society politic – whether from extremists in a religion or a political organisation or, less obviously, from advertisers. Whether enforced or subtly reinforced, homogenisation in groups, societies, or in language can lead to the elimination of whatever is different or ‘other’. … diversity enhances the advancement of our species’ development, the quality of our life on our connected planet, and even our survival. Within this overarching context, we must work to protect and preserve the rich, expansive, un-flattened uses of language. When nurtured, human language provides the most perfect vehicle for the creation of un-circumscribed, never-before-imagined thoughts, which in turn provide the basis for advances in our collective intelligence.”

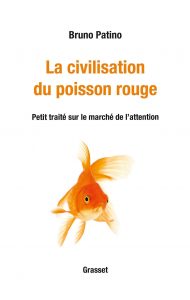

Thus when it comes to digital culture, the huge gains that we are already reaping also have the potential to incur huge losses and these latter are already becoming detectable. In addition to the differences between reading properly from a book and gliding over content displayed on a screen, people’s ability to concentrate and be absorbed in what they are reading or otherwise doing, is being eroded through the habit continually checking their mobile phones. In 1998, the average concentration span of an adult in Britain was found to be ten minutes. By 2008 this had halved, while more recent surveys suggest that concentration may have dropped to a mere two minutes. For Tristan Harris, one-time design ethicist at Google but now the director and co-founder of the Center für Humane Technology (CHT), the dependency of people on their appliances is humanity’s most pressing problem. For Harris parasitic tech platforms are out of control and through the addiction of people to social media pose an urgent, existential threat to society. The root of the problem lies in the use of free services. Funded by advertising, this has resulted in a race for our attention which is the underlying cause for what Harris calls “human degrading”. The Center for Humane Technology is thus dedicated to radically re-imagining digital infrastructure and its mission is to initiate and steer a comprehensive shift towards a humane use of digital technology that supports the well-being of all human beings, democracy and a shared information environment. To join the movement and learn more see: www.tristanharris.com and www.humanetech.com. The theme of human degrading is also explored by Bruno Patino in his book, The Goldfish Civilisation (only available in French). Goldfish kept in captivity are reckoned to have an attention span of eight seconds and so, as they swim round and round their aquarium, experience it as an endless journey of discovery and are blissfully unaware that their boundaries are in fact severely limited.

In a highly disturbing confirmation of the analogy, a study has shown that people who grow up with smart phones expect a new impulse every nine seconds and that if this does not happen their attention begins to wander. The message is that instead of beings equipped with imaginations that have the capacity to soar and fly, we have become goldfish caught in a bowl of glittering devices that confine us. Nevertheless there is hope and with the CHT supported development and release of the record-shattering Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma directed by Jeff Orlowski-Yang, highlighting the existential threats posed to society by social media, an estimated 100 million people were reached.

As Wolf observes, for democracy to work properly, a population must be capable of critically examining the issues and making informed decisions on complex matters without being manipulated by “spin” and misinformation. These fears are corroborated by Maria-Anna Schulze Brüning and Stephan Clauss who in their book, If You can’t Write You’ll be Left Behind – Why our Children Fail to Learn (only available in German), discuss the way in which children learn to write. The context of the work is on the one hand a series of reforms that were supposed to simplify the learning of joined-up writing as a response to older systems being seen as authoritarian and out-dated. It is however also a paediatrician’s reply the lobbying that is going in the German-speaking world for education to be digitalised at all levels without trial programs or indeed without anything detailed having being worked out at all. As one might expect the push for digitalisation in the classroom comes from the IT and computer industries, with teachers and experienced paediatricians being relegated to the side wings of what is an exceedingly dangerous experiment. In their book, Schulze Brüning, who is an experienced teacher and Stephan Clauss, who is a journalist well versed in the field of education, argue that writing and our approach to writing is the result of a physical process that initially involves our whole upper bodies, in particular the hand-eye co-ordination system. It is they argue, imperative that the skill of writing by hand be taught properly at schools. Once mastered, it enables school and learning to be enjoyed and is extremely important in the establishing of an ability to grasp contexts and make connections between things. As the body grows, the brain learns by doing things with its body, in this case the hand and it is only in this way that the motor memory switches of the brain are activated and pathways brought into being that establish connections between things. All too often, Schulze Brüning has observed that children with bad, shaky handwriting, are disadvantaged with the disadvantages not being made up for by the use of digital devices – either in the short term or in the long term. Learning to master the art of writing by hand is not something that has been made irrelevant by the fact that adults generally type rather than write. Rather it is an essential part of a long and complex process in which the whole upper body as a motor organ is involved. Although the struggle is a long and drawn-out process the gains are immense. The ability to use hands and fingers precisely, combined with an initiation into the world of the written word are of seminal importance for any child.

Meanwhile, the mathematician, psychologist and cognitive neuroscientist, Stanislaus Dehaene, observes that when learning to read and write, children must learn to repress a reflex that ignores the differences between left and right. For this reason some children go through a phase when, either occasionally or often, they write words backwards and are unaware of doing so. Learning to write joined-up letters by hand teaches children how letters are formed with the result that the differences between letters such as “b” and “d” and “p” and “q” which are often confused, become apparent. In his book, Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How we Read, Dehaene argues against the use of whole word methods of teaching children to read. Neurobiology conclusively shows that children initially learn to read, decoding words letter by letter and only once this has been mastered do they move on to recognising syllables and whole words at a glance. Attempting to skip the letter by letter by letter phase results in confusion and disadvantaged readers. Although a child first experiences reading in the form of being read to, it would seem that at school, the teaching of reading and writing are to be seen as belonging together. If pupils are to become proficient readers, the learning to write stage is an integral part of the learning to read process. It is only step by step that a child acquires proficiency in understanding what language is, what words mean and how, on paper they may be actively formed and combined to make messages that others can read. Importantly, the gains come in both the short term, such as the triumph of a young child when he or she is able to write their own name, as well as in the future, when books and diaries have the potential to play an essential role in the building up of an inner dialogue that enables us to find out of who we are. Chillingly, Schulze Brüning and Clauss conclude their book with a reminder that in George Orwell’s 1984, it is only when he begins writing a diary in his own hand, that the book’s hero, Winston discovers he has he capacity to think his own thoughts and to lead an inner life.

Even more chilling however, is the fact although Orwell’s prophetic date has long been surpassed and sales of the book have continued to soar, nevertheless three aspects the book are completely overlooked. In 1984 as well as in life, Orwell placed his faith in humanity in the „proles“, or working-class, who whilst engaged in the struggle to live out their lives and care for their families are also loyal to their immediate circles of friends, neighbours and collegues. Yet the classless society of today has largely eroded community feeling and like Winston Smith, we have all become isolated middle-class people alienated and set off against each other by greed and technology. The second overlooked aspect of Orwell’s nightmare vision is the pill that is taken by citizens and which represses their emotions. This is because The Party knows that populations with emotions and inner lives can be troublesome. The relevance of this today is that, leaving aside the issue of smart phone misuse, many of us, both willingly and unwillingly are bombarded by a continual stream of background music. Day in day out, at home and at work, radios and random song-players subject us to a continual stream of acoustic padding which alienates us from what is going on around us as well as alienating us from ourselves. Dampening our ability to respond to music surreptitiously stifles our capacity to feel as important musical markers in our inner world are successively rendered meaningless through over-exposure. Thus apart from, in an obvious way, making critical thinking difficult and impeding deep reading, background music erodes our feelings of self and hinders us from conducting an inner dialogue with ourselves about who we are and what we want.

Roland Topar, illustration from Nouvelles en Trois Linges, 1975

The third over-looked and equally important aspect of Orwell’s 1984 is the fact that history is, what The Party says it is and this is something that is constantly being revised and changed so that from the resulting confusion, the lessons of history become irrelevant. This has disturbing parallels with aspects of the way in which history is dealt with today, which for all the good intentions and re-addressing of biases and prejudices that are intended, nevertheless results in something that at the end of the day, is confusing and uninteresting and so is rendered harmless. For the practioners and sponsors of this form of history, the purpose and point is to show that „we“ in the present „know better“. In this way, both in Orwell’s 1984 and in our own present, the past is dissolved and in a drab and seemingly eternal present, what The Party says, is everything.