Week 1

Following the burning of the Yule Log on Christmas Day, on my console table, the New Year begins not with anything new but with the burnt ash of the old year.

For my forthcoming book, Rediscovering History in Krems and the Wachau, I embark on the task of copying of the scene of the Temptation shown at the beginning of the Krems Bible and which I stumbled upon in Week 42 of 2024.

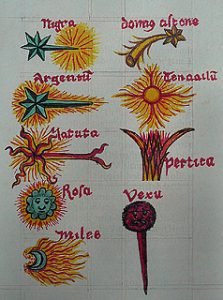

There then follows a copy of Georg Peuerbach’s classification of the different kinds of comet that he had observed. Although depicted as animated and with faces, Peuerbach saw comets as physical entities with predictable orbits that could be calculated and did not see them as portents of the future or indications that divine retribution was at hand.

Last but not least there is a map of the world drawn in 1152 by the Arab geographer, Idrisi, who worked at the Court of Roger II of Scilly. This is significant for Krems as on the map, Krems is one of only three places in Europe that are named, with the other two both being in Italy. Idrisi will have known of Krems from the coins that were minted in the town during the eleventh century.

The Twelve Days of Christmas over, on 6th January, the ashes of the old year are scattered over the beds on all three levels of the garden and on my console table there is but an empty jar.

Week 2

Given The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt for Christmas, I read of how during the Renaissance, a philosophical poem by a master poet was discovered in a monastery in Germany by an Italian book hunter. The poem is De reum natura and the poet is Lucretius. During the Middle Ages, this work disappeared and was very nearly lost. Following its rediscovery, some fifty manuscripts copies were made with one copy finding its way to Aggsbach Dorf in the Wachau.

Here there was a Charterhouse and in a library catalogue complied during the second half of the 15th century, a manuscript of Lucretius is listed. From my own researches I know that the manuscript is not in the National Library in Vienna. Following the Charterhouse’s dissolution at the end of the 18th century, I know that some of the books from the library went to the Abbey of Göttweig that lies across the river from Krems and Sein. Drafting an e-mail, a few days later, I receive the answer that they do not have the copy and furthermore, their helpfully looking in a monastic database on my behalf, has also failed to yield any clues.

In his book, Greenblatt presents Giordano Bruno as if he were an advocate of Lucretius‘ view of the world and of his philosophy. While in some respects these claims can be seen as having some degree of relevance, put the way Greenblatt puts it, this is not correct. Greenblatt bases his claims on Bruno’s The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast. This work is particularly significant as it was the book cited by the Inquisition in Rome which led Bruno to the bonfire on which, in 1600, he was burnt. While the passages quoted by Greenblatt are there, what Bruno thereafter says is omitted and so the passages are divorced from their proper context and from Bruno’s ultimate argument. From the rest of what Greenblatt says on Bruno, it becomes clear that, not content with his otherwise immaculate scholarship, he has included Bruno in his book, as he wanted at all costs to have a martyr in his story.

Following Copernicus, Bruno believed in a world in which the sun was at the center of the solar system and not the Earth. Anticipating the main tents of modern materialism, he believed in an infinitely infinite universe which, as it had neither beginning or end, inside or outside, accordingly could not have either the earth or the sun at its center. Yet Bruno also believed in the objective existence of the countless immaterial relations that pertain between things and in terms of which, in philosophy, the Idea Forms of Plato can be defined. Following on from this, he saw gods and spirits as existing in some way and in The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast points out that the Egyptians and Greeks never worshiped statues as such but rather the ideas and principals that the statues concerned articulated and gave expression to. As Bruno says in The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast:

„Those wise men knew God to be in all things, and Divinity to be latent in Nature, working and glowing differently in different subjects and succeeding through diverse physical forms, in certain arrangements, in making them participants in her, I say, in her being, in her life and intellect; and they therefore, with equally diverse arrangements, used to prepare themselves to receive whatever and as many gifts as they yearned for.“

(translated by Arthur D. Imerti)

Continuing on from this, in other works, Bruno declares himself to be a heroic enthusiast and makes it clear that he saw the Renaissance Magnus, through love and through various techniques, as being capable of ascending up towards the divine aspects of gods and goddesses and from them, on up to the ultimate all all-enclosing One of Being and Truth. This contrasts with the view of Lucretius for whom the gods, if indeed gods there be, are so far away that they cannot possibly be interested in human affairs and so to all intents and purposes are unreachable. Despite their sharing a common starting point, Bruno and Lucretius are worlds apart and it is misrepresenting and callous of Greenblatt to stage the death of someone in a way that is at odds with what they stood and died for.

Week 3

As the year enters its third week, I am still adding missing images to Rediscovering History and whilst things invariably fall into place, new questions keep arising and unexpectedly, the chapter on the Krems apothecary, Doctor Wolfgang Kappler, proves difficult to beat into shape.

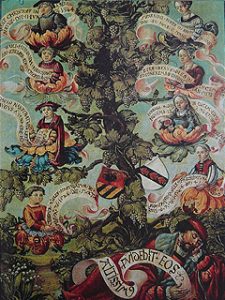

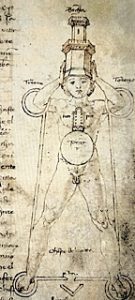

Yet perseverance pays off and reaching out for a book that I bought in Edinburgh over thirty-five years ago, I am rewarded with an insight. This is that a family tree painted on the back of a portrait of Kappler’s wife, was possibly prompted by an image and text from a book by the doctor and alchemist, Paracelsus.

In the first instance my case rests on the fact that the painted image is reminiscent of the engraving in the book, with the pose of Kappler sleeping on the ground being a mirror image of that given in Paracelsus‘ Prognostication of the Future over 24 Years.

Thereafter the text accompanying the image resounds with echoes of Kappler’s personality and of what he was trying to do as a doctor and citizen of Krems. For introductions and a reproduction of the Prognostication see: https://archive.org. Kapppler’s wife, Madalena, was the mother of thirteen children and as the family tree on the back of her portrait only shows eight of them, it is assumed that the picture was painted in 1544 when the eighth child was born.

This means that only the first edition of Paracelsus‘ Prognostication of the Future over 24 Years could have played a role in the conception and composition of the family tree as the other editions all post date 1544. Yet frustratingly,in order to clarify this, I must wait another week.

Week 4

Ordering the 1536 edition from the National Library in Vienna, I make my way to the capital only to be told that for older works, lending conditions now require written letters of application. Nevertheless the trip is not entirely wasted as along the way, I stop at Kirchberg am Wagram and look at Oberstockstall, where during the second half of the sixteen century, a well-equipped alchemist’s laboratory was in operation. Next to the vestry there was a barn where grain was stored, with the roof beams showings signs of smoke, suggesting that this was where the laboratory originally was sited. Like Paracelsus, Kappler was interested in alchemy as a program of bodily and spiritual care and self-improvement and had connections with Christoph von Trenbach who was the owner of Oberstockstall. At Kirchberg am Wagram, the Museum of Alchemy where the finds from Oberstockstall are displayed is being updated and so will not be open for at least another year. Meanwhile, at Oberstockstall although there is nothing to see except an outer wall with a fabric that, for the discerning eye, is rich in history, there is a top-quality restaurant and holiday accomadation.

Lying asleep on the ground at the base of the growing family tree, in his right hand, Kappler holds a scroll with the statement: „Altissimi pudebit eos“. Asking a friend for help in translating the Latin, we arrive at: „From on high he will put them to shame“. This would seem to refer to Kappler’s having achieved something that his successors with never be able to equal. Looking into the significance of the lily of the valley shown at bottom left of the picture, I learn that although poisonous, the plant contains substances that are of medicinal use and during the Renaissance, a number of authors give recipes for making extracts and distillations.

See: https://digitale-sammlungen.de.

As a break from Kappler, alchemy and his big discovery, I read the Die Seelenharfe, „The Harp of the Soul“ by the musician and composer, Gandalf. A tale of a musician finding and then losing himself, the story is a parable from which we can all learn and those who are older, can all relate to. The story is one of inner resonances and of being in tune with the music of the world, followed by a fall and a slow and painful return to that which through the daily grind had become lost. For music composed by Gandalf which was a part of the book’s genesis, go to: https://www.youtube.com (to skip past the advertising by click on „überspringen“). The book prompts me to return to my own inner music and understanding of the rhythms of the year and the cycle of the seasons. Begun in 2023, this was conceived as a form of diary that by presenting a modern day creation myth in monthly doses is able to arriving at a more integrated and balanced view of the year and which is thus able to relates us to the wider and deeper rhythms of life. Although I make progress, I repeatedly stumble and get overwhelmed in the irrelevant details of spurious analogies.

Week 5

In Vienna, I confirm that the last image of the 1536 edition is the basis of composition for all later editions and thus possibly of Kappler, lying on the ground, as shown in his family tree. Ordering a manuscript of medicinal recipes that Kappler bought and to which he then added a large number of other recipes, I search for recipes involving lily of the valley plants. However, despite searching for Convallaria majalis, Liliu covallin and „Mayblomen“ this draws a blank. Instead however, I find something else that suggests that the lily of the valley in the family tree is symbolic and stands for Christ as the Salvation of the World and new life.

The codex is an almost 800 page compilation of recipes that offer cure and relief from all manner of ills and afflictions and the depth, scope and focus of the medical codex make is clear that Kappler was first and foremost a doctor and did not himself have any form of active involvement in alchemy. Thus the puzzle of what the big discovery was that made that made Kappler stand out from his contemporaries still remains and unexpectedly, after a few hours of leafing through the pages, scanning every recipe, I finally find his big discovery. This is a cure for epilepsy which both Kappler and his contemporaries saw as being laden with theological significance.

Week 6

Meeting the sculptress, Susanne Kompast, with whom I had an exhibition in Vienna almost exactly twenty years ago, we talk of a joint exhibition for 2026 and I return to the series of relief’s begun in Scotland exactly a year ago. As my thoughts meander and circle, I decide to throw caution to the winds combine the series of relief’s, with the diary project begun two weeks before and step by step, structure and clarity appear.

Week 7

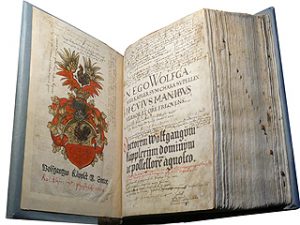

The week begins with a day in Vienna and at the National Library, I re-examine the Kappler Codex and armed with a letter of permission that the dust-jacket be removed from the cover, am able to transcribe the eulogies written by Kappler’s contemporaries on his ability at making medicines and finding remedies against affliction.

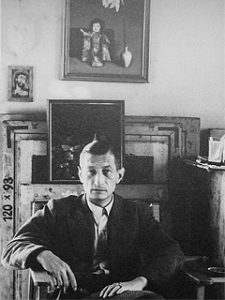

After a quick lunch, I see an impressive show at the Leopold Museum dedicated to the work of Rudolf Wacker, an undeservedly neglected Austrian artist. After an expressionist phase, Wacker embraced Neue Sachlichkeit and painted scenes in which the poetry of things and the world shines through, articulated through detail and subtly coordinated light.

As the curators astutely observe, this phase is concerned with and expresses the transcendent beauty of the world. Yet with the rise of fascism, a sad nostalgia sets in, as it becomes ever clearer there is going to be another war and that the intrinsic unity and poetry of the world is doomed.

As the grandfather of a friend, was a friend of Wacker’s, I have held a Wacker sketchbook in my hands and was acquainted with the artist’s earlier work but not with his Neuesachlichkeit. Translated as „New Objectivity“, the more literal translation of „New Thinglyness“ gets to the heart of the matter in that it implies that poetry and unity are innate in things and that it is four hundred years of modernist and proto-modernist thinking that has led to us losing sight of this. Unfashionable though he may be, this was also Heidegger’s take on things, reality and the constructed versions of reality which we inhabit. An eye-opener, I resolve to buy a catalogue.

In the evening there is a concert by Martin Theodor Gut in Porgy & Bess. Here Martin plays his electric monochord accompanied by a laptop. Using a moveable pick-up and a variety of striking and drawing implements that range from a felt hammer to an industrial spring, Martin extracts overtones in which delicate filigrees of sound alternate with heavy walls of music that bring one face to face both with the delicacy and the metallic rawness of electrically amplified string music. During the evening one gets the feeling of being inside the string and of knowing what at bottom, music really is. Bravo!

The next day, I translate the Latin poems from the Kappler Codex and update the relevant chapter of Rediscovering History in which his big discovery is outlined. Thereafter the week continues with my working on the sculptures that expound a creation myth and provide the foundations for a structuring of the year. Mathematical insights go hand in hand with content and formal issues and suddenly, at week’s end, I have the series planned out with all conceptual issues resolved and a development that leads back to the point where it started.

Week 8

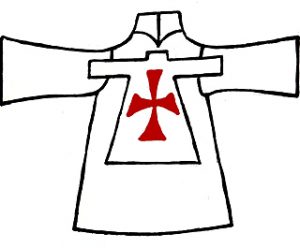

Again the week begins with a day in Vienna, where in the National Library I read a short tract written by Kappler for Maximillian II. The topic is a shirt decorated with Saint George’s crosses front and back and imbued with substances to enhance virtue and godly strength. Supposedly worn by crusaders, the the tract is important as it confirms that Kappler saw the world in terms of physical processes that lead either away from or towards God and the divine.

During the week I update my article on the sculpture Saint Vitus in a Vat held by Museum Krems and aided by town records and plans from the Monument Office identify where, following the Renaissance, the work stood. I also begin work on two new relief’s.

Week 9

On my way to Scotland I continue working on the concept for the series of relief’s representing not only the cycle of the seasons but also the coming into being of all that we know. This is of course a tall order but over the next few days, each day brings progress. Work starts at the airport and as we take off and head North, through the window I see Krems, Stein and the Wachau and realise that my work on a landscape related calendar based on the 13,14,15 triangle with the Steiner Kreuz as center, whilst appropriate and important for me, is not only personal but is also highly localized and it is time for me to move on and formulate a modern and generalized metaphor for God and the divine. Since beginning the project, my faith (if one can call it that) is that in order to be all we can be and should be, we must search for that which binds and holds all that is together. Our powers of reason evolving through evolution so that, by abstracting, we could understand better situations and thus apprehend and avoid danger, it is our destiny and duty that those with the ability go beyond the immediacy of such situations do so and take these powers of abstraction to take their utmost limits. The truths thus found, integrated into the customs, beliefs and institutions of society, would then make a functional (as opposed to a dysfunctional) society. The problem is that today we get stuck in the details and lose sight of where we ought to be going.

In Scotland, at a one time fly-tipping site where old cookers and fridges have lain rusting among the undergrowth, I find heavily corroded plates of metal and laying a few out on the ground, return to my sketch book to find out where they might fit in. My intuition correct, they find their places and after transporting them to my father’s workshop, I cut them down to size with an angle grinder. At the same time, a number of unresolved and highly important issues find resolution and after forty years of searching, I realise that I finally have a mathematically derived philosophy of being. This derives from Parmenides and simply involves tagging his insights onto the digits of what is known as the Morse-Thule sequence. The revelation is that in order to relate the sequence to the philosophy of Parmenides, one should start not with 0 as Morse and Thule did but with 1. Implicit in the awareness of something is the possibility that it might not be and although Parmenides dismisses this, the concept of absence and not-being is hugely important. In mathematics this entails acknowledging the seminal importance of the concept of zero. Thus when Fibonacci introduced the notation of nought and with it the concept of zero, to the West at the beginning of the Renaissance, far from being a trick that merely enabled the abacus and simple arithmetic to be transcended, it was a doorstep moment that opened up the way for later explorations of the infinite and the infinitesimal. Meanwhile in physics, the importance of the concept of absence involves acknowledging the importance of the void. As twentieth century physics has shown, although there is no such thing as the void, the concept is immensely useful and it was only through physicists actively investigating what they imagined to be a void that it was found that it was in fact a chimera.

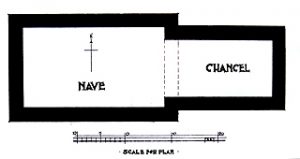

On an old drove road known as the Wheel Causeway, I search with my brother for a Romanesque Church that, once shown on ordinance survey maps, has now „fallen off the map“ and is no longer shown. Nevertheless we seek and in a clearing, among the plough lines of forestry plantation, we find the outlines of a simple church. Later I find the ground plan and see that a carved fragment of masonry is on display in Hawick Museum.

Here again there are vestiges of something far away and almost lost and yet with patience and persistence may be found and in the mind’s eye, reconstructed.

Week 10

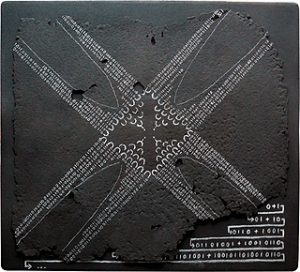

Back in Stein I continue work on the Saint Vitus article. Yet in between times, I mount the plates of rusty metal from Scotland on boards and beginning work on a number, finish one.

This is arguable the most important and is a visual representation of the proof that there is something that mathematicians call a surface of constant negative curvature (SCNC). In geometry, where a circle is enclosed by the plane in which it is drawn and a sphere is likewise enclosed by space, with a SCNC, the situation is reversed and the two-dimensional planes and the three dimensions of space are enclosed by the surface. Whilst this is baffling and results in something that cannot be imagined, it is nevertheless not illogical. Integral to its not being imaginable from within two and three dimensional spaces is the fact that there is only one such surface. Integral to the proof that such a surface exists are systematically generated sequences of numbers which, whilst being aperiodic, are not random. In this context, the most well-known sequence is the Morse-Thue sequence yet others can also be invoked. Starting from zero, the Morse-Thue sequence is generated by taking zero and adding its binary oppose, 1, to result in 01. Then the same is done to 01, to result in 0110. Repeating the operation of copying and inverting results in the next term being 01101001. This results in:

0

01

0110

01101001

0110100110010110

et cetera.

Rendered in terms of a binary mapping, Fibonacci’s rabbits result in 0 becoming 1, and 1 becoming 10. The is results in the sequence:

0

1

10

101

10110

10110101

1011010110110

et cetera.

Like God, the SCNC is all-enclosing and all-encompassing and is beyond space and time.

As they are self-similar, aperiodic, non-random sequences exhibit both local and wide ranging structural patterns that derive from their self-similarity. Thus whilst being aperiodic, the SCNC is not random, yet in the space that is embedded in the SCNC, genuine randomness is possible and as space unfolds, in the forever sprawling vastness of what physicists call „the multiverse“, patches of randomness emerge. These are however so random that instead of containg and even mix, they contain extremes as well. Thus within the vast swathes of semi-randomness, there are patches of pure chaos and absolute order. These are so extreme that they are unsustainable and accordingly come into being and then fade, only to arise again somewhere else. Illustrating this, back in Stein, from a distance of three meters, a row of pebbles on the garden path catches my eye. After ten years of only ever seeing randomly arranged pebbles, I suddenly see four pebbles in a row. Taking a photograph, I later see that there are other rows, including a row of seven pebbles. Thus in random distributions short stretches of order occur repeatedly.

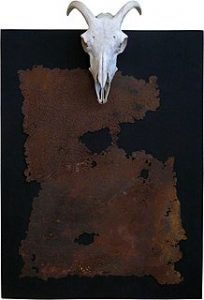

Another piece in the series of relief’s takes this as a departure point and on the calendar introduces Imbolc as „Imbolc“ is Old Irish for „in the belly“ and refers to the ewes that are pregnant at the beginning of February, the piece incorporates a sheep’s skull found in Yorkshire. This piece is however not finished and is awaiting a pattern of copper nails that need to be hammered through the rusty metal. These will represent the way in which, in the multiverse, new universes come into being.

In the multiverse, a patch of absolute order can result in the formation of a supra-hot, supra-dense, crystal, which so perfect that the only thing that can happen is that a flaw emerges and shatters the oh-so perfect order. This results in an exploding universe. As the new universe explodes, it goes from a state of maximum order to the state of maximum disorder, or entropy and so returns to the state from which it emerged. In doing so, over billions of years, it follows an innumerable number of paths that whilst not deterministically predictable, nevertheless follow laws laid down by haos theory. Although a branch of mathematics, chaos theory has so many real world applications that one of the two constants associated with it, delta, is known as the „universal constant“. Reflecting the multiverse and the SCNC that encloses it, when the phenomenon known as „period-doubling“ is analysed and rendered in binary notation, the digits of the Morse-Thue sequence emerge. In like manner, from the binary rendition of Fibonacci’s rabbits, the Fibonacci sequence can also be extracted (see Schröder, Fractals, Chaos, Power Laws: Notes from an Infinite Paradise). The successive terms of the Fibonacci sequence, when compared to their predecessors and successors, quickly approach the ratio known as the Golden Mean, which in many situations appears to function as a strange attractor towards which growth processes are pulled. Such growth processes evidently include some or many (it is not known) of those going on in the human body, resulting in the Golden Mean being a feature of human proportion. This however, emerges not as a top-down theory laid down by abstract logic that lies over growth but rather as a bottom-up principle in which the Golden Mean is striven towards but never perfectly achieved. Reflecting this, the figure of a prophet that I am planning and who begins the series, will have perfect Golden Section proportions. Not yet made, the board against which he stands, is finished.

Week 11

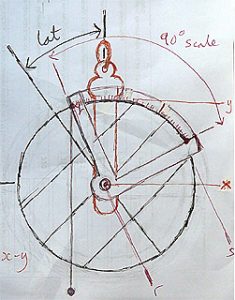

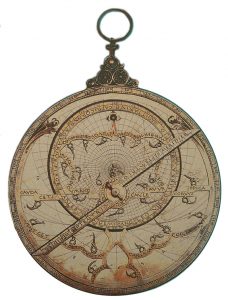

Up until now I have seen the SCNC as a metaphor for something God-like, with entropy and chaos theory being a mantra that point to something higher and all-encompassing, of which we can only apprehend vestiges. Yet reading Sarah Bakewell’s highly recommendable, The Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails, I ask if if the SCNC is not the Being of which all things partake. But then after a few days‘ reflection, I decide, no, it is not. The SCNC really is something well and truely beyond Being, space and the being-there-in-space of an object in space. This was Plato’s position, who in his Timaeus, saw the universe as consisting of Mind Being/Space and Matter that was in Being/Space. The existentialists, in particular Satre, were very much concerned with notions of freedom and free-will. Yet having discovered chaos theory, freedom and free-will are no longer problematic for me and instead, my big concern is integrating ethics and a dimension of self into a materialist account of the world. Via the SCNC, a curve known as a tractrix, an object known as a pseudo-sphere and the fact that all living things are involved with problem-solving, I have a mathematical model of the self in which an ethical axis is embedded. Although presented at a discussion group a number of years ago, I had begun to doubt its relevance. Now, after a period of questioning, I am reassured and know that it truely belongs in cycle of sculptural relief’s. Nevertheless the question is how exactly? This brings me back to the project of constructing an astrolabe in which a subjective dimension of being is integrated and I resolve to put the project on the list of things to do over the summer.

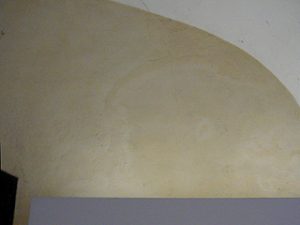

While Rediscovering History in Krems and the Wachau is being edited, I work on the article on Saint Vitus and establish conclusively in which room of the Burgesses‘ Hospice, the sculpture once stood. This insight is gained by comparing the rooms listed in inventories, with plans from the State Monument Office and what can be seen in the original space, which latter is now a public arcade with 24 hour access.

Between the Burgesses‘ Hospice Church and Schmidl’s Bookshop, the walls and the two column that support the vaulting are covered by display cases which make it difficult to get an impression of what once was.

Nevertheless above one of the display cases there are signs that there was once an above eye-level niche at a place that is confirmed by the plans of the building as it was in 1966, before renovation.

This confirms the conclusion arrived at by my analysis of the sculpture itself, with there being very clear signs that the end of the Renaissance, the work was adapted for display at above eye-level height.

Week 12

Despite a cold spell, spring is in the air, work in the garden is resumed and statuary is re-installed. With the end of two book projects slowly drawing near, I begin a new book on a collection of Renaissance sculptures that, during WW II, were sent for safe-keeping to a salt mine in Altaussee. These include the Museum Krems Saint Vitus figure, Michaengelo’s Bruges Madonna and Lorenz Luchsperger’s Apostles in the cathedral at Wiener Neustadt. Reading Sarah Bakewell’s eminently recommendable, Humanly Possible, I find confirmation that what I am planning is in truth, a deeply humanist undertaking. In my book on Altausse, the intention is to combine not only the various stories of events (gripping in themselves) but also character studies of protagonists with whiffs of art history and WW II technology.

Week 13

Finally I succeed in tackling a last methological difficulty in the Saint Vitus article and at the Austrian National Library in Vienna order two obscure works on the lives of Christian saints from which I need to extract more detailed reference information. Again in Vienna, the week ends with a concert of Baroque music in which Reinhard Czasch, leader of ensemble, Ventus Iucundus, makes his last public appearance as a performer on stage. Held in the opulent reception rooms of the Schottenstift Monastery, Czasch and his colleagues give a dazzling display of the interwoven, playful complexity of Baroque music, with a series of virtuoso solos by the retiring flutist. Nothing is forever and the delight of the concert is mitigated by the knowledge that Czasch will be forever stepping down from the dizzy heights of musical perfection that he has attained.

Week 14

Adding the new images and making the last changes to the Saint Vitus article, I submit it to the Krems Town Archive for publication. As it has already been peer-reviewed and accepted, it goes straight on to the proof-reading stage.

Week 15

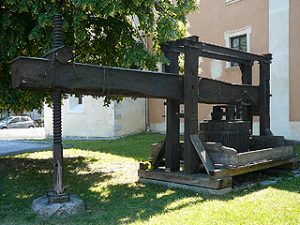

Breathing a sight of relief that at last something is finished, I return to the guide book of Krems and the Wachau and finish typing in corrections from the editing stage and copy the ISBN number into the cover. In the village of Mautern opposite Stein, I notice that an old wine-press I had photographed for the book has been replaced by a sub-station for a new hotel.

Asking if the press will be re-erected elsewhere I learn that it was so rotten that on being taken down it fell to bits! As wine presses in cellars are difficult to photograph due to the extremely cramped conditions, I decide to retain the photograph and amend the picture caption accordingly.

Week 16

At the end of her, Humanly Possible, Sarah Bakewell addresses the rut that contemporary humanism has got itself stuck in. Although she knows no solution other than to keep striving and indeed this is very much the point, nevertheless the problem is one of „For what exactly are we to strive?“ As identified by Bakewell, the rut appears to be formed by a willingness not only to see another person’s viewpoint but also to accommdate it. While a willingness to see and understand the views of other people is essential to humanism, accommodating all other viewpoints amounts to trying to be all things to all people. This can then only result in something that repeats the Universal Declaration of Human Rights but does not go any further, as doing so it would invariably infringe in some way on the feelings and sensibility of someone else. While we undoubtedly need a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the fact that we live in a globalised world does not mean that there is then a culture and way of behaving that is based around a set of ideas and things that everybody can embrace and intellectually and emotionally relate to. Rather, this can only ever be partially the case. Taking a purely intellectual example, the One World Pragmatism expounded on the Reloading Humanism Mission Page will not appeal to those who do not and cannot follow abstract mathematical arguments drawn from the western scientific tradition. Whilst one can formulate a pan-human, world ideal, the details of how such an ideal is to be attained are and must be formulated in regional, local culture terms. Yet here one can legitimately ask: „What does this mean exactly?“ With respect to life in the modern world, Charlie Chaplin said, „We think too much and feel too little“. The challenge of humanism today is to high fly in our minds whilst at the same time cultivating and having hearts that are capable (in theory at least), of reaching out to all of the people in our immediate vicinity. Through in practice we can only emotionally relate to a limited number of people, through our relationships with the people whom we care for, we can take part in cultivating a culture in which care could in theory be extended to all people, with the „in theory“ being an ideal that we hold dear even though we cannot come anywhere near to implementing it to its full extent. Thus at the end of her book, Bakewell returns to a favorite and highly relevant quote from Robert G. Ingersoll that encapsulates this in a masterful formulation:

„Happiness is the only good.

The time to be happy is now.

The place to be happy is here.

The way to be happy is to make others so.“

Week 17

With respect to the Ingersoll quotation given above, Bakewell say, „It sounds simple; it sounds easy. But it will take us all the ingenuity we can muster“. Continuing on from Chaplin’s „we think too much and feel too little“, one must observe that we are also i) complacent, lazy and cowardly and ii) consumed with cynicism. On the one hand we think too much, on the other, when we do think, we don’t think properly. Pursuing ideals and striving to make sure that those who come after us will have a future and that whilst we are alive, we do not knowingly or unknowingly, exploit either other people or nature, is hard work and repeatedly calls on us to make choices that we would much prefer to sweep under the carpet and ignore. By embracing an attitude of pseudo-intellectual, superficially staged cynicism however, we can say that, with respect to the manifold problems of the world, both at large and before our noses, there’s nothing we can do and that all things come to an end anyway. Taking this attitude then enables us to comfortably continue indulging in i). This is the great myth of contemporary culture which ultimately rests on a cynical, distorted view of evolution. According to the myth, we are lost babes in the wood, abandoned as orphans by evolution as a cruel joke in a world that cares but nought. This is not only false with respect to evolution, it is also deeply romantic and thus is by no means as savvy and cynical as it pretends to be. It is also nausiatingly self-staged and narcissistic. Scientific studies undertaken in various fields, using various techniques, have shown that when there is enough to go round, human beings are altruistic. Further we do care about others and those who help others have been shown to have enhanced senses of well-being when compared with people who do not actively help others. Here „helping others“ means helping, real, physical people. When it comes to long-term well-being, working for an ideal is no substitute for genuine human contact. Nevertheless, as the great myth was brought about through intellectual activity (combined with a lot of stasis), it must accordingly be countered by intellectual activity (without stasis) as well as other means (such as art, literature, film and theater). Thus at Reloading Humanism the avowed aim is to forge and propagate a new conception of who we are and what we can be.

Missing Piero after so many months work on Rediscovering History in Krems and the Wachau, I am intermittently able to return to him and to the not insignificant role he plays in Art and Mathematics in Krems, the Wachau and Borgo Sansepolcro. Prompted by Piero, I re-examine my treatment of Archimedes in the book and I see that a long sought facsimile of the copy that Piero himself transcribed is available – only at a price and I dither. The choice is complicated by the fact that, both at the Library of Congress and at the Riccardiana Library in Florence, the work is available for scrolling through on-line: teca.riccardiana.firenz.sbn.it. Is this enough or would holding his book in my hands bring me closer to him?

Week 18

Returning to Bakewell’s Humanly Possible, the Robert G. Ingersoll quotation and Bakewell’s cautious proviso, „It sounds simple; it sounds easy. But it will take us all the ingenuity we can muster“, I am perturbed that such wise words should then be followed by the Humanists UK logo. Although Humanists UK have a number of important campaigns running, something about the site disturbs me which is symptomatic of modern, secular humanism. By disavowing the fact that the first humanists were mostly believers, secular humanism has disconnected itself from history. More often than not, secular humanism is infused with notes of „but we known better (than to believe in religious twaddle)“, with this there comes a form of latent complacency that is at odds with a striving for that which is good. Here the word „striving“ means that the going will not always be easy and accordingly there is no room for complacency. Historically, Renaissance humanists had to argue that what they were doing was not un- or anti-Christian. Taking the idea of pre-figuration, in which events in the Old Testament are seen as anticipating events in the New Testament, the first humanists argued that the principle of threefolded-ness that is a feature of Plato’s philosophy, was an anticipation of the Holy Trinity. From this they then argued that the gods of Greece and Rome were anticipations of aspects of Christianity. Zeus they argued was equivalent to God the Father, Christ was equivalent to Apollo, while the Holy Ghost was equivalent to the Good of Plato. Via the Greek gods and their obviously human natures, humanists were then able to emphasize the human aspects of life and living that during the Medieval Ages had been dismissed and denied importance. Humanism was thus born of argument and debate and not from complacency. Continuing this theme, Humanists UK are also utterly uncritical of what technology is and will do to us. For Tristrian Harris who once worked as a design ethicist at Google, the problem of the stupification, or „human de-grading“ that the overuse of digital technologies is resulting in, is not a major problem, it is THE PROBLEM. If we cannot solve the problem of human de-grading, we will not be able to solve the long list of other problems that we have. As one of their mottos, Humanists UK has the exhortation: „Think for yourself, act for everyone“. For an organisation that claims to encourage free and critical thought, the failure to even acknowledge that not everything that technology does to us and for us, is for our long term good, is remarkably uncritical. Carrying this gross oversight over into the realm of aesthetics, their logo visually panders to the design aesthetic of the multi-national companies who are doing so much not only to exploit environments and peoples on the other side of the planet but also their own employees. Not want to harp on and generally rant and rave, I give an example and rest my case (BP left, Humanists UK right).

On a positive note, confirming that Humanists UK in particular and secular humanism in general, has lost sight of what is needed and conversely, that Reloading Humanism is on the right track, on the internet I find an article entitled „Humanism Reloaded“ by Marco Russo. Published by the Forum for the Humanities in Slovenia, this shows that there are difficult abstract problems that need to be addressed. Associate professor in Philosophy at the University of Sorento, in Italy, Russo argues that the European humanist tradition does have something to offer in the articulation of a conception of humanity that paves the way for concepts and formulations that go beyond the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To this effect he identifies a striving for virtue as being essential, with this arising not by itself out of nowhere but through personal human interaction. In Humanly Possible, this is identified by Bakewell at the beginning of her book, when she introduces E. M. Forster’s exhortation: „Only connect!“. This rings like a refrain, not only through the pages of Howard’s End but also of Humanly Possible. Yet it is precisely here that digital technology is undermining our trust and good-will and so our ability to connect and relate to one another. Thus a critical view of digital technology must be part and parcel of any serious debate on who we are and where we are going. For Russo’s article, Humanism Reloaded, see: for-hum.com.

In Museum Krems I photograph a bronze sculpture of the god Amor, whose posture is strikingly similar to the figure of the Humanists UK logo. The Roman equivalent of Eros, the capricious juvenile is the personal assistant of Aphordite, the goddes of love and luxury. Also know as Cupid, Amor traditionally shoots arrows at people that cause them to fall in love. Yet in the Museum Krems sculpture, he has exchanged his bow and arrow for a bolt of lightening. This he has acquired from Zeus, ruler of the gods and stands not only for power but also for the knowledge that lies behind and enables power. During the Renaissance, following the teachings outlined by Plato in his Symposium, love was seen as having the capacity to lead a person from a yearning for the body of another, to a yearning for beauty in general and from there, to a yearning for beautiful ideas and understanding. In the sculpture, that is dated to around 1600 and thus dates from the end of the Renaissance, Amor is shown making this transition. No longer blind-folded, he stares ahead in awe and amazement, not at the thunderbolt in his left hand but into the distance, at the beauty that understanding and knowledge have brought him. Yet his face shows that there is something else going on and he is beginning to realize that with knowledge and understanding, there comes power and responsibility. This is emphasized by the fact that in his right hand, he still holds the end of the band that once covered his eyes and he realizes that he must now use the band to keep the needs of his body in check so that he may use the power and knowledge he has acquired responsibly.

Appropriately this echoes the themes of the last few weeks, for in a world in which everyone talks about rights, it is significant that no one talks about the responsibilities that go with the freedom that rights entail. This is my whole gripe with Humanists UK and their abrasive secularism, for if one is going to abandon religion, then it is not enough to campaign for rights and then leave people to the whims of contemporary consumerism and the conception of life that tech companies have thought out for us. Rather I for one, think (and feel) that between moments of laughter, humor and joy, one should endeavor to take things seriously and strive to formulate a regionally grounded conception of humanity that brings dignity, wisdom and responsibility back to life. This indeed is shown in film and script-writing where a good comedy will have an alternating series of up’s and down’s that give depth and drama and so enable humor to unfold and take us by surprise. While Humanists UK may ultimately be striving for gravitas (or at least not wanting to exclude it), it is not communicated by the texts and visuals of their website and this to such an extent, that after repeated visits, I still feel uneasy each time I visit their site.

Week 19

Still nagged by doubt about what exactly it is that I find problematic about secular humanism and knowing that it is to do with a lack of striving and a misplaced abundance of complacency, I recall that in all households where a western lifestyle is led, there are a number of machines that do work which, two hundred years ago would have been done by a number of full-time servants. This is the work done and speeded up by washing machines, vacuum cleaners, central heating and cars, not to mention a host of lesser gadgets. While materially this represents a huge step forward, we have not stopped to think that if each of us has a team of servants working for us, then it behoves us to try and cultivate the gentlemanly, noble aspects of ourselves and to give something to the world and humanity that makes up for the spread of luxuries that have been served up to us on a plate. This is the now time-honoured observation that whilst we have made unparalleled technological developments, our emotional intelligence and the culture it which it is embedded and which has the capacity to shape and form it, have lagged behind. It is also the issue of gaining freedom but forgetting that with freedom there also comes responsibility, encountered in Week 18. Thus if we are to have a future, we must do all we can to ensure that instead of being a vapid form of entertainment and a road to stupification (as at present), culture once again becomes a survival technique that ensures that what we do and what we think and believe are brought back and held in a form of balance that ensures the health of the eco-systems that are essential to our survival. Regardless of whether one sees culture as a battle-ground either for against stupification or as a work in progress, it is clear that if one accepts the urgency of the environmental dilemma and of stupification, there is no room for complacency and that our actions must be guided by something that goes beyond the superficial, instant gratification happiness of consumerism and which takes into account the health of our planet and the lives and futures of future generations. With its zealous emphasis on secularism and the rights of the individual, secular humanism shifts attention away from the two central issues of our time and glosses over the fact that humanism was born from an ideal of striving for things and understanding that takes us beyond ourselves and it is precisely this that we need if we are to develop a genuinely sustainable culture. Lying behind this is the fact that in bringing about a supposedly classless society, striving for excellence, ideals and genuine understanding has become lampooned and everywhere there is a tendency to reduce things to a lowest common denominator. This of course includes the arts, areas in which historical humanists were very much interested. Yet in discussions on humanism, whilst literature is mentioned and correctly seen as a extension of humanism, the fine arts are routinely ignored, raising the highly pertinent question of „Why?“ Here it quickly becomes evident that both modern art and contemporary art (they are not the same) are what Bakewell would call „anti-humanist“. They are enterprises of abstraction, in which the interest is in formal games and in pseudo-intellectual, semi-critical processes of reflection and staged „discourses“, which have nothing to do with human beings as people, endowed with feelings and sensitivities. This brings the matter back to Chaplin’s „We think too much and feel too little“. In becoming modern, we have become ashamed of being human.

Working on the possibility that the astronomer, Regiomontanus may have been in Urbino, I find that one of the manuscript versions of his Epitome is in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. This was made for Queen Beatrice of Hungry with an image of the first page being at: digital.onb.ac.at. The Epitome is an updated version of Ptolomy’s Almagest, with the immense task of translating, commenting upon and updating Ptolemy’s masterpiece, being done by Regiomontanus in Rome, where he stayed as a guest of the exiled Greek Cardinal and Bishop, Bessarion. As the work’s sponsor, when it was finished in 1461, Bessarion will have received a suitably smart presentation copy from Regiomontanus. Yet he was also given a second, more modest version which is now in Venice: ptolemaeus.badw.de. This features a dedication to Bessarion written in Regiomontanus‘ handwriting as an afterthought. This is important as in the dedication, Regiomontanus calls himself „Ioannes de Kunigsperg“, so that the initials on an astrolabe that was made in Urbino in 1462 and which features the initials „KP“ may have been made or commissioned by Regiomontanus as a present for Duke Federigo da Montefeltro of Urbino and thus be indicative of Regiomontanus‘ having been there.

Whether Regiomontanus was in Urbino is relevant as whilst there, he may have met Piero della Francesca and talked with him on the nature of curved and straight lines and whether they were equatible or whether they were really two completely different kinds of entity. Where Archimedes and Regiomontanus thought that they were equatible, Cusanus argued otherwise. While Piero’s view is unknown, analyses of a number of his paintings suggest that he might have have been in agreement with Cusanus.

Week 20

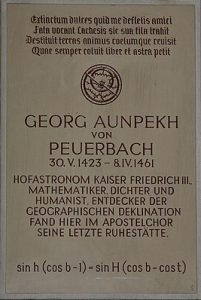

For Art and Mathematics I work bachwards from Regiomontanus, to his tutor and colleague, Georg von Peuerbach who as an outstanding mathematician was buried in Saint Stephan’s Cathedral in Vienna with an epitaph that records his achievements: court astronomer, mathematician, poet and humanist. Discoverer of (the laws lying behind) geographic declination.

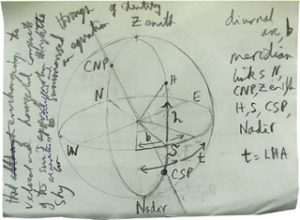

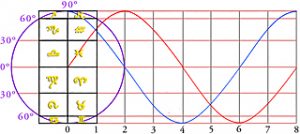

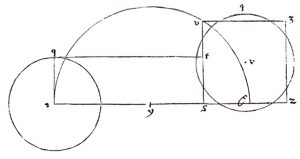

In order to understand these latter I do a drawing.

Then I turn my attention to Peuerbach’s predecessor, Johannes von Gmunden. Likewise a mathematician and astronomer, Johannes von Gmunden devised a calendar that circulated widely during the fifteenth century. In this way, I am brought back to the problems of the calendar and the difficulties of calculating the date of Easter introduced in Rediscovering History in Krems and the Wachau. No longer content with understanding the nature of the problem, I now want to understand the solution without the shortcuts offered by tables, which whilst handy, hide what is going on in the mathematical background. Happily I find a resource and understanding sets in: almenac.oremus.org.

Week 21

While I work on the graphics for the chapter on Johannes of Gmunden, a bound proof of Rediscovering History arrives. Although I am happy with the lay-out, there are so many mistakes in the text that a second reading by someone who has not already read the book is necessary. Happily, the editing of my article for the Town Archive is slowly approaching completion and the editor is glad to proof-read Rediscovering History.

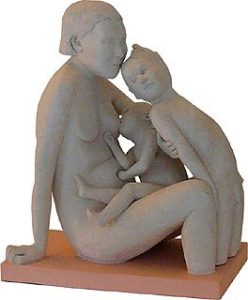

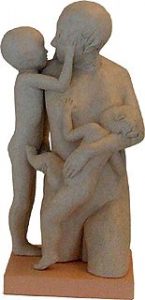

In Museum Krems an exhibition opens which shows exactly the dilemma in which artists today find themselves in. Whilst upstairs in the main gallery Judith Ziller presents a series of works based on a face taken from a Byzantine icon, in the cloister of the Museum Krems she exhibits two mother and child groups. Where the works upstairs struggle for some form of vapid intellectualism, the sculptures on the ground floor are rooted in genuine feeling and experience and say things about motherhood and bringing up children that have not been given form before.

Week 22

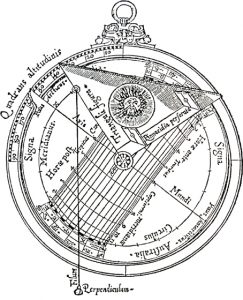

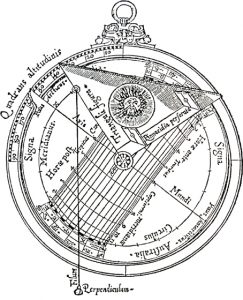

After Johannes of Gmunden and the problems of the calendar, the astrolabe as introduced in Codex Yale 24 by the Czech mathematician and theologian, Christian de Prachatizt, becomes the focus of my attention and I begin a step by step guide on the geometry of the instrument, filling in what de Prachatizt and other dialists invariably gloss over.

Continuing the theme of the dilemma faced by artists today, in an interview, the renowned sculptor Tony Cragg, observes that the formula for success in Britain, is a cocktail that is heavily laced with social issues, as typified by Gilbert and George, not to mention Brit Art. In his adopted home of Germany, this attitude is much less prevalent, with this being something that he values. This indeed has always been my problem with Britain and the Anglo-Saxon world; everyone behaves as if there is and can be no other reality than the social reality constructed by human beings. Thus political correctness and identity issues in our neck of the woods are accorded more importance than the global consequences of our actions and no one stops to consider how, via our lifestyle, we exploit and inflict misery on people on the other side of the world and live as if hell-bent on destroying our environmental niche. As sketched out in „One World Pragmatism“ on the Mission Page, I see chaos theory as a mantra that we must adopt if we are to stop destroying the one and only environmental niche that we have. The fragile symphony of stability that, as the universe proceeds from a state of maximum order to a state of maximum dis-order, chaos theory engenders is akin to the stacked forms created by Tony Cragg, resulting in columns that are balenced and yet precarious, static and yet dynamic, with this reaching back to the ultimate miracles of life.

Echoing and underlying the over-emphasis on social issues, for those in the know, the attitude to life is that there is no secret to life, no ultimate goal and there is nothing we can do except passively accept the cynicism that is the hall-mark of modern culture. Here the sub-text is: „If you can’t handle cynicism then you’re not up to negotiating your way through life and accordingly are a failure“. On this view, there is no truth, no secret and all is for nothing, with life being but a meaningless process of dog eat dog. Yet from the history of the calendar, I see that there are things and realities that go over and beyond us and while a definable, ultimate reality may not be obtainable, that does not mean that it cannot be approached. Thus the synchronization of a macrocosmic definition of a second (the ephemeris second) with a microcosmic definition (the caesium second) in 1960, was and is a very real achievement even though now, as Martin tells me, ever improved accuracy in measuring is bringing uncertainty to the latter. Moreover, in endeavoring to describe the realities that lie beyond the social realm, the history of science and technology show that very real changes can be brought about in realities that include the social realm (and indeed it is these changes that are the root of the environment’s many problems). Thus although there is no easily definable secret to „life, the universe and everything“, the secret is that in searching for a secret, if we are persistent, we will find. And whilst in later decades, what we discover may be replaced by something more sophisticated, the point is not the acquistion of an absolute truth but rather the striving for it with, apart from any material gains that might be in the offing, the striving also having the capacity to give us inner confidence and so help make us better people, with this being the real point and the real gain, not only for us but for „life, the universe and everything“.

Week 23

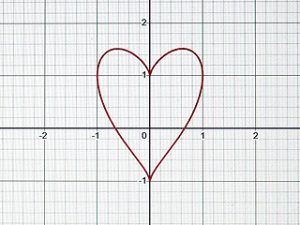

After a decade of living in Krems, I finally get around to writing down a piece of graffiti written on a sub-station:

Typing the formula into a mathematical graph program, I am rewarded with:

Whilst Rediscovering History is being proof-read I take the chance of clarifying a last remaining detail and from the Danube, walk up through the woods towards the old Roman road that leads from Melk to Mautern. The track I follow is an access road by means of which the Roman fort at Bacharnsdorf was supplied and manned and the purpose of my trip is to establish the exact route as the information is not marked on maps.

11th June, 2025

Lying low in the sky the full moon is tinged with red and yellow and won’t be this close to the horizon for another 19 years when the Metonic Cycle repeats itself. This provides a fitting end to my work on the calendar and for the book, Art and Mathematics, I move on to the Controversy of the Doctrine of Learned Ignorance. Here I have the feeling that something is missing and looking on the Internet, I find what I am looking for. Cusanus was short-sighted and wore glasses made from beryl. At the end of the Controversy, he then used his myopia and the corrective measures brought about by concave and convex curves as a metaphor for the geometry he was developing. Although the beryl that was used for making Cusanus‘ glasses was pure, tainted with impurities, beryl often has an amber hue, like the moon of June 11th 2025.

Week 24, 2025

Slowly both my article on Saint Vitus and Rediscovering History approach completion and I am busy with proof-reading and checking and re-checking references.

Reading the diaries of Rudolf Wacker, my thoughts repeatedly return to a vision of society articulated by Wacker in 1920 during his internment in a POW camp in Siberia. As an officer, Wacker did not have to work and as the camp was miles from anywhere, the prisoners were often allowed to go out for walks and to visit the town where Wacker was able met other artists, patrons and was allowed to borrow books. Not experiencing the Russian Revolution of 1917 at first hand but nevertheless only one step removed from it, he was fully aware of the potential for change that it brought. Yet he also knew that a society without hierachies could only result in a lowest common demominator in which life was demeaned of value. Thus in Tomsk, he wrote:

„Looking below the surface, in as far as culture enables an investigation of the self to be undertaken, it is the most valuable, complex and intensive undertaking we have, with potentially far reaching results for development of personality. From this point of view, culture is an undertaking to which all political and social endeavours must be subordinate to, being means to an end and not ends in themselves. The French Revolution broke the rigid class divisions of society, now it is the privilages that capitalism has introduced that need to be dissolved. We want the most flexible system imaginable, that guarentees each and all all, every chance of education, with a filter that ensures that only the talented and hardworking get to the top. There should thus be a top and a bottom, not a formless form of equality and the differerences between individuals should be to be as large as possible. Those at the bottom however, should have a guranteed existence that ensures that they are healthy and well-fed, have adequate housing and enough time for rest and relaxation. In all walks of life, getting to the top must depend on the quality of what an individual delivers, lack of money should never be a barrier. I am thinking of society as a pyramid, not made of blocks of stone but rather something like this: a shimmering, changing, flowing form of life, each individual held in check by his or her weakness, all promotion being the result of individual effort. At the top there are the most intelligent, those who carry culture, at the bottom those who are less individualised, who are accordingly less developed.“

During his earlier years, both in internment and afterwards, Wacker influenced by Expressionism, from which he then later freed himself, with being anticipated in his diary a few months afer the above quote.

„There is too much violence in Expressionism – practically a rape, so that the soul is left out and bodily depictions of love are raw. This over exaggerated emphasis on the subjective is to be understood as a reaction. We must find a middle way and plumb deeper into the depths of ourselves and have a deeper, more intimate contact with nature and grow with and in her, piously worshipping her.“

Week 25, 2025

In Upper Austria, I at last get around to visiting the town of Peuerbach where there is a museum dedicated to astronomy and the exploration of space. Only open on a limited number of weekends each year, the museum is well laid out and presents the history of astronomy via well-chosen exhibits and informative texts: peuerbach.at. Next to the museum there is the town hall, topped with a larger than life size copy of an astrolabe that Peuerbach made and which is now on display in the Geman National Museum in Nuremberg.

When open, the museum offers the services of an excellent guide who is not only passionate about astronomy but also does not shy away from the philosophical questions that cutting-edge astro-physics raises. These in turn raise further questions about truth and society and in my notebook I write:

„In a healthy culture, there must be something that the culture revolves about, which goes beyond the mere possession of wealth and the exercising of power. This other must be an ideal which is striven and any society that forgets this is in the long term unsustainable.“

„The secret behind society is not that there is no secret and that nothing adds up, but rather that assuming that things do add up and searching for a better means of addition will, if we are persistent, result in just that and for a while, will yield just and bounteous rewards even though what we find will one day be superceded. Thus it is all a matter of faith and searching and ignoring the cheap, tasteless cynicism that eats away at us from inside and which only ever gives superficial rewards.“

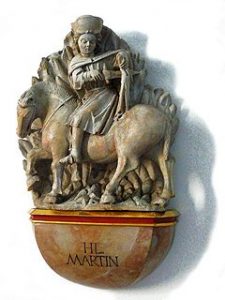

Meanwhile in the town church, a Renaissance sculpture of Saint Martin is as good as, from a photograph, I was hoping. The image shows the Saint in the process of divding his coat in two so that he may share it with a beggar who has nothing, not even clothes.

Week 26, 2025

The next week I am in Altaussee, taking photographs for „Undercover, Under Wraps, Underground“.

Altaussee is watched over by a broken tooth of rock high above and by a long cliff that runs along the southern side of the lake.

Week 27, 2025

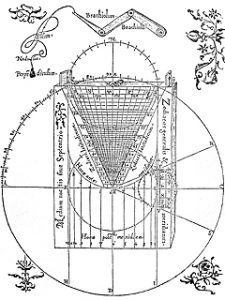

A book on Peuerbach arrives and slowly I work out the import and real message of a tract written by Peuerbach in Codex Yale 24 and which features an instrument known as a universal astrolabe. Far from being a quaint work on an ancient instrument, the tract shows that Peuerbach knows that the instrument embodies the geometry of sines and cosines, with these lying behind the sun’s apparent motion in the sky according to what is now expressed as: sin h (cos b + 1) = sin H (cos b – cos t) as inscribed on the memorial plaque dedicated to the astronomer in Saint Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. In the story of western science this is a seminal moment as it is the first time that sines and cosines are used to summarise a regularity occurring in nature.

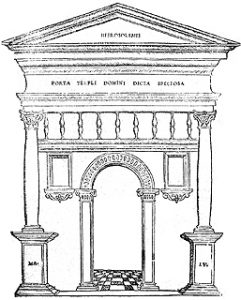

A universal astrolabe of the type described by Peuerbach as depicted by Orance Finé.

Week 28, 2025

In Melk, I photograph and examine an astrolabe and quadrant from the beginning of the seventeenth century and establish that it may well have been made at the monastery following the instructions given by Christian de Prachatiz in Codex Yale 24.

Week 29, 2025

Continuing the Altausseer Land theme, the highlight of the week is an open air screening of Vom ewchem lem, a series of interviews woven around a concert held on the shore of the lake the next to Altaussee. This is the Grundlseee and the concert is a form of folk/pop/country music performed by the quartett, Molden, Resetarits, Soyka, Wirth. While Viennese folk is not necesssarly my thing the people, Molden’s songs and their playing together are absorbingly authentic, with the direction by Jürgen Moors being focused on the people being portrayed, what they are doing and the place where they are doing it.

Week 30, 2025

At last Rediscovering History in Krems and the Wachau arrives and I immediately begin to start dispensing sample copies to bookshops and retailers in the area. Thereafter a list is drawn up of Lord Mayors and people in local politics to whom copies are to be sent.

Week 31, 2025

Slowly Rediscovering History becomes available with Matilda’s Books, Treasure, Events and Buchhandlung Schmiedl leading the way and the monastery at Göttweig and Buch am Berg (in Furth, at the foot of Göttweig Hill) following a few days later. As the week progresses, the trail of bookshops stocking Reloading History slowly works its way upstream to Dürnstein Abbey and the Shipping Museum at Spitz.

At long last my article „Complex Geometrical Constructions in Renaissance Works of Art: the General Context and a Case Study in Krems“ is uploaded and published as a Mitteilung by the Stadtarchiv or town archive. See: mitteilungen.at.

Week 32, 2025

After a manic week of marketing both Rediscovering History and Complex Geometrical Constructions, by way of a break, I return to an object made ten years ago which two years ago I took to pieces and remade but then never finished. An astronomical dial, the instrument was intended to combine mathematical exactness with poetic resonances brought about by the design and the spaces suggested by the geometry that makes the instrument work.

The instrument is a Regiomontanus sundial that has been inverted with the grid being used to suggest the perspective of a tiled pavement as in the archway that in Luca Pacioli’s Divinia Proportione of 1509, precedes the geometrical solids of „God’s Kingdom of Well-Shaped Forms“.

For hundreds of years, astronomical instruments made of brass were state of the art measuring devices that although ornamentated, were very much associated with the purose of measuring and quantifying the world. Nowadays we perceive such instruments at one remove, and whilst distanced from them, are able to register and respond to formal features that were back then lost amid the purposes and uses that were their raison d’etre. Thus we can go back and recombine the mathematical and the poetic, with the now finished front-side of the instrument being a form of manifest.

To this effect, for the back, I write a poem describing how, once the instrument has been used to ascertain the time of day, other soundings and measurements should be made, not in the world at large but within the uncharted realms of the self:

To find the hour of day…

To find the key that unlocks the staid world of form

and which truely maketh both space and time dissolve,

use the counter-weight to plumb lost and silent hours

that amid dark beginning’s and lost destainies

you will find answers to the unasked questions of

who it is thou art and what thou wouldst most well do.

All this accords well with Rudolf Wacker’s concept of the „thingly-ness of things“ and with Martin Heidegger’s notion of „things in themselves“, this latter not being a hidden world of essences but rather things as they appear to us, unencumbered with the precepts of use, function and social meaning that we project onto them and via which, we see and all too glibly judge the world.

Week 34, 2025

Finally I work out what the instrument described by Georg von Peuerbach on pages 437- 445 of Codex Yale 24 is. See: collection.library.yale.edu (digital pages 457-465). It is nothing other than the original design of the universal sundial described some sevety years later by Orance Finé in his Four Books of Solar Horology.

This might sound about the most obscure and irrelevant thing imaginable, but behind the recognition is the realisation that Peuerbach has designed the instrument so as to articulate something for which mathematics at that time did not have the tools to describe as easily as we can today.

This is the seminal recognition that sines and cosines can be used to describe phenomenoa in the natural world, with the squashed together spacing of the lines at the edges of the rectangular shape at the centre of Peuerbach’s instrument, reflecting the peaks and troughs of sines and cosines, when the differences in successive values are less than in the middle of the cycle.

Week 35, 2025

The week begins with a sketch of the universal sundial described by Peuerbach and ends with a concert. In between however, there is:

Black Saturday

Unwelcome but not entirely unexpected, the dreaded day arrives when my 25-year-old Apple Mac, after ten days of fitful starts and strange freezes, stops working. From a Doctor Norton analysis carried out via a CD-ROM start, I know that there is no hope of recovery. The good news is that the 40 GB data disc has only some minor damage, offering the hope that its data can be rescued. The next day, at the 2025 Am Sound Festival for Micro-Tonally-focused New Music, bewailing my loss, I am offered a replacement by a friend who is moving house and has one computer too many.

As every year, Am Sound is held in the Gothic chapel known as the Ursula Kapelle which is otherwise not open to the public and in amid the filigral of the chapel’s vaulting, there follows a mesmerising concert for piano and harp.

Week 36, 2025

Am Sound continuing, the week begins with a concert for accordian and theremin. Played by Otto Lechner and Pamelia Stickney, in their Meander, the two virtuso musicians evoke a series of musicscapes which repeatedly remind me of the enigmatic object mathematicians call a „pseuso-sphere“.

Week 37, 2025

For Art & Mathematics I sketch out the history of sines, cosines and tangents and juggle the details of Peuerbach’s and Regiomontanus‘ lives around the mathematical content of what I am introducing. Online resources play an important part and I am able to look at Renaissance manuscripts that document, some of them sumptuously, the history of mathematics and astronomy.

See:

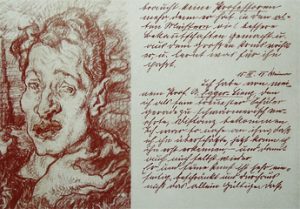

I also struggle with Regiomontanus‘ handwriting:

www.deutsche-digitale-bibliotek.de

and in Vienna find an article that puts the astronomer’s letter to the mathematician, Christian Roder, into a much needed context.

Week 38, 2025

The arrival of autumn is greeted with a wreath sent from Upper Austria. Although a facsimile of Piero della Francecsa’s copy of Archimedes was ordered weeks ago, it has so far failed to appear and I begin to worry and wish that I had ordered from a more expensive dealer (such as: ziereis-faksimilies.de), rather than going for a cheaper source in another country. Have I been conned? Politely pointing out to the seller that six weeks have gone by and I have not received the book, without any explaination or apology I get a refund and am left to work out what has been going on for my self. The answer is probably that the seller never had the book but rather had two copies reserved. In the meantime inflation has kicked in and the price has doubled!

Thus I am left with a choice of two online versions or of digging very deep into my pocket:

teca.riccardiana.firenze.snb.it

Despite this lack of the last piece of the Piero della Francesca jig-saw, I write a history of his and Regiomontanus‘ knowledge of Archimedes and out of a messy jumble of highly obscure details, manage to extract a story that says something about the two men and their respective quests. On the facsimile front, I see that all suppliers are now offering Piero’s work at twice the price as hitherto. Evidently the explaination is that inflation and probably decling turnover too, have taken their toll. Thus I am left to dither about paying twice the price or waiting to see whether the work will one day be available second hand.

Week 39, 2025

After an interruption of some six months, I finally get back to my translation of Cusanus‘ Quadratura circuli of 1453 and continue the task of checking my ropey Latin-English translation against a much more reliable Latin-German translation. I am also relieved to find that the mathematical issues are already resolved and everything is so to speak „squared“.

Week 40, 2025

In the Scottish Borders I climb Brugh Hill on which there is a stone circle.

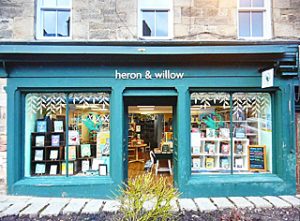

On another day, in Jedburgh, I visit Heron and Willow, a bookshop situated in the heart of the historic town: heronandwillow.scot

Browsing aimlessly I, find a book on Stalin’s library and the owner’s reading habits. Written by Geoffrey Roberts and entitled Stalin’s Library, the blurb o the back says that although Stalin hated his enemies, he hated their ideas even more and, an avid reader, in as far as they wrote books, read them. At the time of his death, Stalin’s library numbered some 25,000 books, periodicals and pamphlets. Significantly, 400 works are annotated with notes which show that, as the author says, „Stalin was a serious intellectual who valued ideas as much as power.“ This reminds me of another, not unrelated book, The Philosophy Steamer: Lenin and the Exile of the Intelligensia by Lesley Chamberlain. This describes how, in 1922, Lenin had all the philosophers, writers, journalist and scholars in Russia with whose ideas he did not agree, put on a ship for deportment to western Europe. Thus prompted, I decide to put both books on the Christmas list for Santa Claus.

Week 41, 2025

Back in Krems, I restructure Art & Mathematics and find the long sought ending for the work that unites Renaissance mathematics and modern mathematics. I also see that apart from the thought-out but not yet executed end, only biographic sketches of Regiomontanus and Cusanus are needed to bring the work into a rounded, consistent whole.

Aware that the historic astrolabe made by Regiomontaus for Cardinal Bessarion, that was once in the National Maritime Museum in Grenwich, was sold at an auction a year and a half ago to an unknown bidder, I am relieved to find out that the new owner is the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Whilst no longer in Europe, this fascinating astrolabe has at last been seured by an institution for the common good.

For auction information and articles by the autioneer see:

Week 42, 2025

In the Town Hall, Rediscovering History is officially presented to the Lord Mayor, Peter Molnar, the Councillor for Culture, Elisabeth Kreuzhuber, and the Head of the Cultural Office, Gregor Kremser:

Work continues on Cusanus and as I revise the chapters on his mathematics, its relevance to The Controversy of the Doctrine of Ignorance becomes ever more apparent. Also brought more clearly into focus is the likelihood that Cusanus and Piero della Francesca met in 1458/1459, when Piero was painting frescoes in the Vatican and Cusanus was acting as stand-in pope. This raises the question of whether they discussed art, mathematics and theology and how geometry could be used as a means of appproaching God and whether Piero was familar with Cusanus‘ writings on the subject.

Week 43, 2025

Analysing the diagrams of Cusanus‘ mathematical writings, I find what I had not even dared to hope for: indirect but compelling evidence that Piero and Cusanus did meet and talk of how geometry could be used as a means of appproaching God, appropriately this comes in the form of a geometrc diagram. At long last, Rediscovering History makes it into the shopping window of Schmiedl’s Bookshop on the High Street in Krems.

The week ends with a concert in Vienna by Gandalf, a composer friend in Krems who chose his stage name long before Lord of the Rings became so well-known.

The piece performed is Eartheana, a global journey through the six inhabited continents of the world that ends with a prayer and hymn of hope from the lost continent of Atlantis. Keyboards and guitar are played by Gandalf, accompanied by the Big Island Orchestra and featuring special guests to articulate the unique feel of each continent. When two friends first suggested the idea of a musical journey around the world, Gandalf was first skeptical but then he thinking of Dvorak’s New World Symphony, he realised that whilst describing America, the work is nevertheless unmistakably Slavic. Then he thought of film music, which whilst set to describing whatever needs to be described and given further articulation, is nevertheless recognizable as film music. Drawing from film music, Eartheana opens with a theme, that having announced itself, then weaves its way around and about the movements that describe the individual continents. For the Americas a variety of Native American flutes are played by the acclaimed Native American flute player, Wolfsheart. For a journey along the Silk Road, a guzheng is played by Yu Gong while an impression of Australia is rounded out and given a vibratory, songline-like feel by didgeridoo-player, Otto Trapp. The prayer and hymn of hope is then sung by Eva Novak. In a world torn apart by hate and such obviously superficial and manipulated prejudice, it is a relief to return to a global vision of what the world could and should be.

Week 44, 2025

Unexpectedly I find myself writing about Piero della Francesca’s The Flagellation. Unlike 46 other people writing on the picture, I do not to see the work as a „who dunnit“ in which it is the job of the art historian turned detective to identify each person depicted and deliver a sterile, cut and dried explanation of what is going on. Instead I see the work as a plea for more debate and discussion on what is to be done about the plight of the Byzantine Church following the fall of Constantinople to the Expanding Ottoman Empire in 1453. While the status of the Byzantine Church 500 years ago is not of direct relevance to us today, the current climate of fanatic dogmatism in which rational debate has become as good as impossible, is unfortunately more than topical.

Week 45, 2025

Seeing the three foreground figures of The Flagellation as personifications, I arrive at them representing, Rhetoric, Truth and Virtue and googling the triad, Google’s artificial intelligence software sums up my thoughts admirably:

„Rhetoric, truth and virtue are interconnected concepts, with virtue ethics shaping rhetoric’s aim to persuade through reasoned, truthful, and well-intentioned arguments, not just clever tricks. For a speaker to be virtuous, they must possess „rhetorical virtues“ such as sincerity, accuracy, and good judgement, and believe their message is true and beneficial, even if the audience doesn’t have perfect knowledge. The relationship between them is a subject of philosophical debate, but the modern view emphasizes training rhetoricians who are good people, not just skilled communicators.“

This answers the question posed and raises a host of other questions, which whilst unrelated, are highly topical.

Week 46, 2025

Following Reinhard Czasch’s retirement from public performance with the concert reviewed in Week 13, and the dissolution of his ensemble, my project of organizing a CD of music that over the centuries was composed and played in Krems, is pushed a good few steps back and comes close to falling over the brink into oblivion. In the process of marketing Rediscovering History however, I talk with Alfred Endelweber, the former choir master of Krems Parish Church. In the 1960ies, he tells me, he himself had produced an LP of historical music in Krems and is happy to lend it to me. However before I can listen to music for which I have scores but cannot read, I must have the LP digitalised.

Journeying not as far back in time, after three years planning the new „Time and History Lab“ in Museum Krems opens and the dark secrets of Krems‘ Nazi past are aired, with a critical dialogue being initiated along with the all-important important reminder that democracy is something that must be maintained, cared for. It is not something that once inherited can be accepted as „given“, it and the ideals on which it rests must be cultivated and constantly worked towards. This sounds like a Sisiphosic tread-mill and yes, that is what it is, must be and must remain. There are no short-cuts and democracy at the push of a button can only be a sham. For democracy to be, there must be a culture that supports and nurtures it. And yes, democracy is a fragile and precious flower.

Week 47, 2025