As the permafrost that had been the hall-mark of the Ice Age thawed, the landscape of snow and ice gave way to a new environment. Meandering over its flood plain, the Danube brought into being a plethora of islands, ox bow lakes, marshy patches and bogs. For ten thousand years these appear to have been left largely undisturbed and even for the Romans, the River Danube was first and foremost a boundary. Thus the first people to settle permanently on the river’s northern banks were a people known as Slavs, who from the later years of the Roman Empire up until the tenth century AD, lived in small hill-top settlements that overlooked the river and its wetland landscape. Uncontrolled and uncontrollable, for thousands of years, the Danube was free to meander this way and that over its floodplain and only with the introduction of steam shipping in the middle of the Nineteenth Century was the river regulated, with all that was awkward and irregular being removed. Of the Danube as a convoluted river with a host of wooded and marshy islands, today only a few short segments remain. One such is situated on the bend between Rossatz and Dürnstein where there are two islands, known as Pritzenau and Venedigerau or “Pritzen Marsh” and „The Venetian Marsh“.

Similarly, once numerous and extensive, regularly flooded areas of woodland, dotted with ponds and patches of marsh and bog, are now scarce and limited in size.

On the northern slopes of the Danube, signs of human habitation do not reappear until the arrival of Slav farmers, who between the sixth and ninth centuries AD, lived in small hill-top settlements that overlooked the river. Evidence of a Slav settlement and cemetery found in Stein, suggests that in Krems, where evidence of a cemetery has also been found, there was likewise a settlement.

A Slav mill-stone and examples of pottery on display in Museum Krems

The Slavs were however driven away by invading Magyars who, pushing on into Germany, were eventually defeated at the Battle of Lechfeld in 995 by the forces of the soon to be Holy Roman Emperor, Otto III. Following this decisive victory, a decree was issued and a program of colonisation in the Danube valley was initiated, with Krems being specifically named and recorded as being at the eastern end.

A copy of Otto III’s decree is on display in the hallway of the town hall in Krems. The original is at the German State Archive in Munich

The program consisted of the king’s granting land to monasteries in Southern Germany that they might be cultivated and settled. In this way, the Krems area and a significant stretch of the Wachau Valley were transformed into a patchwork of vineyards owned by different monastic institutions. Craftsmen and traders were attracted and slowly law abiding communities were established. As this progressed, an essential feature of any community was the outlook tower that was manned by a look-out who would raise the alarm whenever bands of brigands or the troops of marauding armies were sighted. It was from such a tower that the Wachau received its name, for the word is an abbreviation for die Wache in der Au or, „the watch tower in the marshes“.

The first mention of Krems dates from this time and describes the settlement as orientalism urbs que dictur Chremsa which means that the town had a fortified place of refuge where citizens could seek shelter in times of unrest. This will have been a form of stockade situated on the south-eastern-most point of the rocky outcrop that overlooks the Krems and Danube rivers, where today the Burggasse, or „Castle Lane“, may be found. Meanwhile, on the Hoher Markt, or „Upper Market“, markets were held. As the town grew, the simple palisade was replaced by a more substantial structure which, more worthy of being termed a „castle“, was situated further West. Consisting of defensive pallas and two towers, it eventually became absorbed into the fabric of what is now the Gozzoburg.

A glimpse of the Gozzoburg from the Untere Landstrasse

In addition to a castle and a market place, to the north-east, the settlement had a church and a watchtower with the lower part of the tower of the Piarist Church, featuring Romanesque windows that hint at the tower’s older origins and function. The original church, which was dedicated to Saint Stephen, can also be assumed to have stood on the site of the current Piarist Church. Of unknown origins but clearly dating from this period is an isolated architectural fragment in Museum Krems, that depicts a harpy.

Like the Romans before them, the newly established monasteries used the Danube as a means of transport and the wine produced by the vineyards was sent up river by boat to the parent institutions back in Germany. On the return journey, salt was carried downstream. This came from Hallstart and was shipped in small craft along the River Traun to Linz. There it was transferred to larger vessels and carried along the Danube. From the fourteenth century onwards ironware was shipped down the River Ybbs to the Danube. For hundreds of years, the Danube was shallow enough at Krems,to be forded by horses, so that the town lay on a crossroads formed by an East-West waterway and a North-South land route that, linking Prague and Vienna, continued on to Venice. As trade flourished, the community grew, with craftsmen and merchants settling below the castle on the South side of the settlement. From these first houses, stairs lead up through the roofs and into the cellars of the castle above, where refuge could be sought in times of attack. By 1014, the settlement had grown to such an extent that land was granted to the church so that a larger building might be built. Situated immediately below the original church, it was not until a century later that the new church was completed. Built as a Roman basilica, the new church was dedicated to Saint Vitus and was linked with the old by two stairways.

Either side of the Gozzoburg, two roads led down to the new district that was growing along what is now the Untere Landstrasse. To the south-west, the Althangasse and the Marktgasse lead to the Täglicher Markt that lies at the western end of the Untere Landstrasse. At the end of the Althangasse, where the old town bordered the new, the windows of old shops testify to what was once a meeting place and shopping area. On the other side of the Gozzoburg, the Wegscheid leads down to the eastern end of the Untere Landstrasse.

Between 1120 and 1193/94, coins were minted in one of the castle towers. These were known as „Kremser Pfennige“ and the reverse often featured a depiction of a walled city with gates. The existence of a city-wall and gateways is attested to in documents that date from 1188 and 1193 so that the city depicted on the town’s coins can be assumed to be Krems itself. Meanwhile the obverse often showed a figure holding two lions by their tails or a figure engaged in combat with a lion. As a result of Kremser Pfennige speading abroad, „Garmisia“ was the only European settlement outside Italy that the Arab geographer, Idrisi gave a name to on his map of the world of 1153.

During the later part of the twelfth century, there was a pause in the town’s growth. In 1196, in recognition of the size and importance that it had attained, Krems was made a judicial seat, with the judge having a sword as a symbol of office. As of those sentenced to death, only clergymen and nobles were eligible to die by the sword, common criminals were hung, this taking place on the north-eastern outskirts of the town, on the rise known as Gallows’ Hill, where the prehistoric figurine known as „Fanny“ was found (see the article An Ice Age Corridor for more).

With the end of the twelfth century, the thirteenth brought a second phase of expansion and from the South, the new town grew out towards the West, with the Untere Landstrasse being extended to form the Obere Landstrasse. Towards the end of this phase of expansion, in around 1250, a third fortification was built. Built on the corner of the Havnerslurche, now known as Hafnerplatz, this guarded the south-western corner of the town. On the South side of the square two Medieval buildings may be seen. The one on the left used to be a chapel and it is around the corner from this building that the outer walls of the fortifications and the defensive structure known as a pallas may be seen.

To counter the rising threat of heretic sects, Dominican monks were summoned from Hungary and a church and monastery were built. Begun in 1240, the complex appears to have been complete by 1260. Unlike other religious orders, the Dominicans built their monasteries close to the settlements where they intended to preach even if, as was the case in Krems, this meant building outside the city walls. In times of attack, the monastery would be abandoned and monks would enter the town through the “Preachers‘ Gate”. Today the church and monastery complex are where Museum Krems is located, with the historic buildings and cellars being noteworthy in themselves.

The Dominican Monastery complex

During the thirteenth century, the castle that overlooked the town was bought by the judge and tax administrator, Gozzo, who radically rebuilt the structure, changing it from a defensive bastion, into the Medieval palace that is named after him.

During the second phase of expansion, Krems was a part of Bohemia. In 1283, aware that the loyalty of his Austrian administrators was not necessarily something that could be counted on, Ottokar II of Bohemia had Gozzo taken captive and held as hostage for a year. Following his release, as an expression of his thanks to the Virgin Mary, Gozzo had a fresco painted in the Dominican Church. This showed Maria as the Queen of Heaven with scenes of the Crucifixion and the Last Supper painted below. Next to the figure of Gozzo, the letters „G“, „O“, „Z“ may still be made out.

During the fourteenth century, the area towards what is now the Steiner Tor was partially occupied and as the century drew to a close, a new western gateway was built.

Where the two round towers are original, the central square structure was built a century later by Emperor Friedrich III. Above the entrance to the southern passageway, the letters „A“, „E“, „I“, „O“, „U“ may be read, carved in stone. These stand for Friedrich’s not unambitious motto „Everything (earthly) Is Under Austrian Omnipotence“. To the North, the city walls were extended so as to include the Dominican Monastery while to the South, the area between the new gateway and Hafnerplatz was encompassed. Close to the Steiner Tor, in the Schwedengasse, a fragment of original wall has survived.

If one follows the Schwedengasse South, turns left at the Ringstrasse and left again at Gartenaugasse, one finds the Mühlgasse on the immediate right. Here a square tower and a half-round bastion indicate the line of the extended southern wall.

During this third phase of expansion, the town was also enlarged out towards the East and the North, with the city walls being shifted out accordingly.

When in 1457, Ladislaus Posthumus died unexpectedly, a dispute arose between Emperor Friedrich III and his brother, Albrecht VI, about who should take over the Bohemian and Hungarian crowns. In the dispute the Viennese renounced their loyality to the Emperor and favoured his brother. At first Krems and Stein followed suite but then, deciding to remain loyal to Friedrich, sent 90 soldiers to help relieve the Empreror who was being besieged in the castle known as the Hofburg in the centre of Vienna. The challenge to power thwarted, when the dispute was resolved, as a sign of gratitude Krems and Stein were allowed to use the imperial double-headed eagle as a coat of arms and it is for this reason that still to the day, in both towns, manholes frequently feature a double-headed eagle.

In addition, the two towns were granted a number of favours and privileges that greatly enhanced prosperity. These included the right to insist that all goods passing through the two towns should be offered for sale for a certain amount of time ̶̶ only being allowed to proceed onwards if no local merchant was interested in buying them. These privileges initiated a period of an economic boom and during the sixteenth century, affluent citizens would send their children to universities as far afield as Padua in the South and Jena in the North. Trade contacts extended from the Mediterranean to the North and Baltic Seas. Those who could afford to, wore cloth from Flanders and seasoned their food with spices that were imported from the East via Venice.

During this time, houses in Krems and Stein, were modernised and those prospering from the new wealth, would buy up adjoining Medieval houses and convert them into single, spaciously laid out dwellings. The facades of these houses would be adorned either with sgraffito or with sculptures and frescoes. Towards the eastern end of the Untere Landstrasse, a number of houses date from this period. On the northern side, there are two houses with first floors that jut out over the street. Of these, the eastern house, Untere Landstraße 69, is decorated in sgraffito. Built in 1561, it is known as the Small Sgraffto House and shows fables and scenes from daily life and the Old Testament.

At Untere Landstraße 56, above the chemist’s shop, there is a fresco of a wine-grower with a vine. Further on, at number 57 on the other side of the street, there is a house with Late Gothic window frames that also date from this period. Retracing one’s steps to Untere Landstrasse 52, there is the Gattermann House with an ornately decorated bay-window built on a corner and which extends over two stories. Both round and rectangular bay-windows were built so that proud house owners could look out over the street and show themselves to the world.

The Gattermann House

Here wealthy citizens known as „burgesses“ would meet and over a glass of wine in a convivial and sophisticated environment, would discuss politics, topics of the day and themes that interested them. By the sixteenth century, Krems was home to some 2,000 people and the burgesses were the wealthy and privileged citizens who ran the town. In addition to the town’s administration there was also a poor-house which was run by the burgesses and the parish combined. The burgesses also contributed funds to a variety of causes, such as the building of hospitals and the adornment of churches. In 1559, 29 burgesses met in the Gattermann House, each drawing, as a record of having been there, their coat of arms on the upper part of the wall. By no means confined to Krems, the burgesses owned a house in Vienna, where they could stay for prolonged periods of time and play a part in national politics and policy-making.

An important feature of Renaissance architecture was the opening up of courtyards, with arcades and loggia’s on first floor. Thus the back of the Gattermann House (Drinkweldergasse 2) features arcades that run in parallel along the first and second floors.

Like bay-windows, these again enabled residents to see and be seen, yet they also allowed rooms to be accessed individually, so that with the new architecture, there came an increase in privacy. Meanwhile oven-builders had perfected the art of making stoves that, sending smoke and toxic emissions up the chimney, generated a warm and cosy heat in which reading and discussion could flourish.

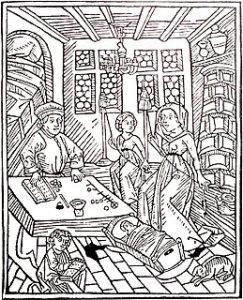

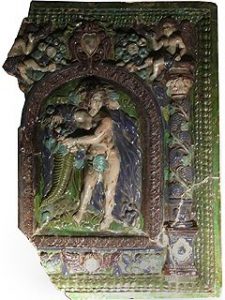

In a woodcut from the period, a merchant and his family are shown in a „Stube“ or sitting room which is heated by the stove depicted on the right-hand side. While the merchant attends to the accounts recorded in a ledger, his wife and daughter are engaged in spinning, whilst before him a boy is shown reading a book. Meanwhile, the youngest member of the family is being rocked back and forth by his mother in a cradle on the floor. As shown in the wood-cut, on the outside, the outer lining of such stoves was formed from tiles which after being clamped together, were bonded and sealed with clay. In Museum Krems a number of ornate oven tiles are on display in the cellar, with the most ornate example dating from the Renaissance.

In this way, during the Renaissance, atmospheres were brought into being in which reading, discussion and private study were engendered and fostered.

Apart from the burgesses‘ Stube or clubroom, there were other clubs where educated gentlemen could also meet and discuss themes of interest, including the things they read in books and the new religious ideas coming from Germany. One such club was the so-called „Siman Club“ which is first recorded in 1529 and appears to have ironically styled itself as a club for hen-pecked husbands. Thus where the Wegscheid meets the Untere Landstrasse, a stone sculpture made by Karl Bauer in 2008, shows a man kneeling in front of his wife as he begs for the key to their house. This is Siman and his wife is resolutely laying down the conditions of his being allowed out at night.

The house at Untere Landstrasse 43 is also of interest as on the Wegscheid side, a derrick can be seen extending out from the attic. By this means, commodities could be hauled up into the attic and stored. This once common feature, serves as a reminder that the wealth of Krems and Stein was built on trade and on the local merchants‘ right of purchase on all goods that passed through the two towns.

At Untere Landstrasse 9, steps lead up towards Althangasse and the Hoher Markt. If the winding steps are followed one arrives at the Large Sgriffto House with sgraffito decorations spread over two stories. As at the Small Sgraffito House, here there are fables, scenes from daily life and scenes from The Bible. There are also scenes of a merchant’s journey to Russia.

Returning to the Untere Landstrasse, at the Täglicher Markt, the Obere and Untere Landstrasse meet and from the North, the Marktgasse leads onto the Täglicher Markt. As its name implies, at the Täglicher Markt, a daily market was held and the crossing was an important intersection and each of the four houses was adorned with a personification of one of the seasons. Thus above the apothecary, there is a personification of Summer, whilst the house diagonally opposite shows Winter warming his hands over a brazier. As the effigies were painted, Summer, having a dark tan, was referred to as a moor and the apothecary on the ground floor is known as the Moor Apothecary. Today the original statue, complete with its paint can be seen in Museum Krems.

In 1532, the house was destroyed by fire as on the Obere Landstrasse side, below the statue, an inscription reads:

In this year of 1532 when Emperor Charles waged war against the Turks, this house was burnt down but within two years, Wolfgang Kappler, medicus, built the same.

Around the corner, on the Marktgasse side, above the personification of summer, there is a relief that depicts a wild man, who in one hand holds a pruning knife, whilst in the other he supports a coat of arms.

Born in Strasbourg, Doctor Wolfgang Kappler evidently came from a wealthy family as he had been able to study medicine in Venice. Thereafter he practised as a physician in Brno, before moving to Znaim, where he practised as an apothecary. In 1527, he received an invitation to be made a burgess of Krems, should he chose to move there. Accepting, Kappler bought the house on the Täglicher Markt and moved with his family to Krems.

A portrait in Museum Krems shows him wearing a red beret, which, like the book on which he rests his hands, shows that the person depicted is someone of education. To his left, there is the Kappler coat of arms with a black cockerel set against a red background in the upper half and green and gold diagonal in the lower half. Kappler’s arms were bestowed upon him by Emperor Charles V and are among the 29 arms that adorn the burgesses‘ club room in the Gattermann House. Of Magdalena Gmundner, little is known except that she was the daughter of a baker and the mother of the couple’s thirteen children. A portrait of her that is likewise on display in Museum Krems and which is possibly by Wolf Huber, shows her in her best clothes, bemused at what was evidently an unaccustomed moment of peace.

At the Täglicher Markt, the top of the house on the south-western side is ornamented with coats of arms whilst below, Medieval and Renaissance images are combined and juxtaposed.

Originally emblems of the aristocracy and landed gentry, since the late Middle Ages, coats of arms were bestowed with increasing frequency on burghers, this emphasising their position and status within the community. In attune with Renaissance thinking, this social context is multi-leveled and the relief of the Kappler coat of arms supported by a wild man is sending out a number of messages. As an outsider, Kappler had moved to Krems on the condition that the town’s doctors would send their patients to him instead of making the remedies themselves as before. Although this was assured and agreed to, on a number of occasions he had to protest that the arrangement was not being adhered to. In the historical record, Kappler therefore comes across as argumentative and difficult. Yet one can equally say that he was simply ensuring that that which had been promised to him was not diluted or taken away. As the wild man looks out over the Täglicher Markt, Kappler is not only announcing himself as a burgher to those of lower status, he is also and perhaps more importantly, announcing himself to his fellow burgesses as someone of standing and substance, someone who can have a burnt-down house rebuilt in two years, as someone who will stand up for his rights and as someone who is knowledgeable and in touch with the latest philosophical thinking that influence and affect all life. To see how Doctor Kappler says this and to find out more about his wife and family see the article „The world’s a Labyrinth! Krems and Stein during the Renaissance“.

Next to the once colourful house on the Täglicher Markt, there is the Gögl House which is graced by a Late Gothic bay-window which formed the eastern end of a chapel.

Continuing on along the Obere Landstrasse, if one turns left into the Dachsberggasse, two more arcades may be seen. On the left, there is an impressive courtyard with strikingly impressive arcades that extend over two stories. Supported by carved columns the coats of arms of the people who lived there are rendered in sgraffito.

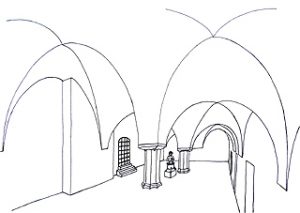

On the other side of the street, looking onto a courtyard with modernised facades, there is a much more restrained arcade with simple rounded arches. This was a part of the Burgesses‘ Hospice which, together with the parish, was maintained by the burgesses, for those who were benefit of those who were old, sick or infirm. First mentioned in 1212, associated with the poor-house cum hospital, were houses and vineyards that provided an income with the whole being run as a charity. Following the Hussite Wars, the number of old, wounded and crippled people meant that a larger premises was needed, with this being completed in 1470. Entering this courtyard and approaching the Obere Landstrasse by turning right, leads to a vaulted arcade.

From 1470 up until 1970, this was a closed space that provided direct access to the Hospice Church. Where two doors on the left led from the Hospice into the function suite, the single door on the right leads to the Church.

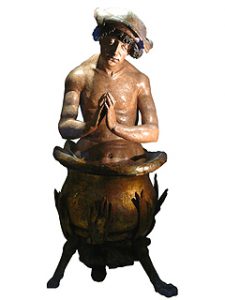

In around 1520, it was for this space that a masterpiece of northern Renaissance art was made. Carved from wood by an anonymous artist, the sculpture shows the patron saint of Krems and can be seen free of charge in Room 2 of Museum Krems. According to Christian tradition, refusing to renounce his faith, Saint Vitus was martyred by being placed in a vat of boiling oil. Praying for strength to withstand the torment to come he was instead miraculously saved by a swarm of angels who lifted him up to heaven.

The patron saint of dancers and apothecaries, Vitus was said to have cured the son of the Roman Emperor, Diocletian, of epilepsy and so was seen as a healer of the malady who could also invoked in cases of dancing mania.

As the only large vaulted room in the hospice it can be assumed that this was where residents ate their meals and where the statue once stood, so that everyday those who lived and worked in the complex will have been confronted with a sublime image of the town’s healing saint. Meanwhile, for the burgesses who used the room as a function suite, there was more going on, with the composition of the work and the triangle formed by the cauldron’s feet, pointing at hidden secrets that only those in the know were privy to. For more on this see: The Triangle and the Saint from Krems on the Reloading Humanism Mission Page. During the Second World War, the work was entrusted to the Ancient Monument Office for safe-keeping and was stored at Altaussee in a salt mine. Offering ideal storage conditions, the mine was soon after reserved for the Führersammlung, the museum that Hitler intended would one day out-shadow the Louvre and the Uffici. Thus during the war, along with thousands of other art works from all over Europe, the sculpture of Saint Vitus in a Vat shared a space with Michaelangelo’s Brugges Madonna, Leonardo da Vinci’s Leda and the Swan and Vermeer’s The Artist in his Studio. For the full story of the art hoarded at Altausee, see: The Triangle and the Saint from Krems.

Continuing on through the arcade leads to the Obere Landstrasse and turning back to the right, one is confronted with a Late Gothic doorway. This is the outside entrance to the Burgesses‘ Hospice Church. Dedicated to Saints Phillip and Jacob, like the hospice complex this was built in 1470 by the parish and the burgesses. Prior to their being expelled a hundred years earlier, the site of the hospice had been where the Jewish Quarter was situated and while the hospice was being built, a pot of gold coins was found. This the burgesses argued was a sign from God, indicating that a church should be built ̶̶ using the gold that divine intervention had provided. Not fully convinced, Emperor Friedrich III saw the find as his and invoking Treasure Trove, only agreed to donate 150 Gulders towards the building of the new church, with his contribution being attested to by the A,E,I,O,U of his motto carved above the doorway.

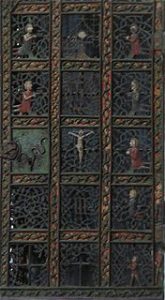

Inside the church, although the Baroque furniture dominates, a Renaissance detail that deserves to be pointed out is the tabernacle on the right-hand side of the main body of the church. At a synod decision made in 1274, it was decreed that in the Diocese of Passau, the consecrated but not yet dispensed sacraments, were to be kept in secluded space protected by an ironwork grill. There thus arose a tradition of making intricate wrought-iron grating’s which lasted up until the sixteenth century, with the Burgesses’ Hospice Church in Krems providing a fine example.

Although it cannot be seen at close quarters use the zoom of a camera or phone to look more closely. At the top Christ is shown as the Judge of the World, while below there is a monstrance with Maria and Saint George either side. In the next row there are three “IHS” symbols, which stand for, in hic salus, which means, “in this sign”.

Below, these invocations are followed by scenes from the Passion and hunting scenes. Above, between the Gothic pinnacles, a six-winged cherub announces the presence of God and bestows blessings.

On the other side of the Obere Landstrasse, there is the back of the Rathaus or Town Hall, with only a double-headed eagle at the entrance to number 4 hinting that this is a municipal building of significance. At the other end of the building, however, opposite the Bürgerspitalkirche, there is a clearly civil and sumptuously ornate bay-window. Featuring coats of arms and reliefs of two soldiers, the structure is supported by a sculpture of Hercules fighting a lion. This stands for the strivings of the city and its burgesses in tackling the problems that confront it.

Originally situated in the old town, the Rathaus was moved down into the heart of the new town during the Renaissance. This was following the donation, by a burgess couple, of the entire block of houses to the town. Following the Kirchengasse up a slight slope, leads to the Pfarrplatz, on the South side of which, a short flight of steps leads up to the Rathaus and passing through the glass doors, one enters a large hallway with a vaulted ceiling. Here the columns are notable, as their capitals betray a lack of awareness of the difference between Romanesque capitals and the Greek and Roman originals that comprise the three orders of classical architecture. This ambivalence is important, as it gave northern Renaissance architects and masons the chance of inventing new forms, resulting in architectural gems such as the Toll Collector’s House in Stein.

The Pfarrplatz is dominated by two churches. High above, there is the Piarist Church, with the tower from which a watchman once looked out over the town. Dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the church is built in a Late Gothic style. Although this appears quintessentially Medieval, in architecture, the Late Gothic is integral to the Early Modern Age in the Krems and Wachau region and is widespread in church architecture. Its elevated position underlining their status, during the Renaissance, the church was the burghers’ favoured place of worship. Towards the end of the period, it was also the official place of worship for the Protestant community.

The Reformation is generally accepted as beginning in 1517 when Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg where he was pastor. The invention of printing by Gutenberg in the middle of the previous century meant that ideas could be easily propagated so that as a countermeasure, in 1528 a decree was issued stipulating that within the Habsburg Empire, a printer could only set up shop in the capital town of a region. This was to make it easier for authorities to keep an eye on what was being printed. Yet against the flow of ideas brought down river by ships, the decree was powerless and during the Renaissance, pamphlets circulated and travelling priests preached, bringing Luther’s ideas of reform to the heart of Catholic Austria. In Krems and the Wachau, these ideas took hold to such an extent that by the end of the century, at least half and quite possibly the overwhelming majority of the population had become Protestant. Thus in 1574, the Church of Our Lady was declared the official place of worship for the protestant community in Krems. As the Protestants constituted a major part of the population, the Parish Church of Saint Vitus fell into a grave state of disrepair. When Maximilian II died in 1576, he was succeeded by Rudolf II (1552-1612), who like Maximilian had Protestant sympathies. Yet Rudolf’s brothers did not share this attitude and were instrumental in promoting the Counter-Reformation in Bohemia, Hungary and Lower Austria. In 1589, the citizens of Krems and Stein were urged to return to the Catholic faith but in an act of open defiance refused. For this they were punished and after a four-year trial, in 1593, the privileges that they had enjoyed for over a century, were taken away. As wealthy Protestant merchants left, the prosperity that the two towns had enjoyed, began to plummet. After Rudolf’s death in 1612, his brother and successor, Emperor Matthias (1557-1619), relented and in 1615 restored the towns‘ privileges. Three years later however, the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) broke out and the downward spiral continued. In 1616, the Jesuits, who throughout Europe were vehement in implementing measures of the Counter Reformation, were allowed to take over the Church of Our Lady and the last unrepentant Protestants, left Krems in 1624. Associated with the rise of Protestantism in Krems was a rise, not only in the reading of religious texts of a protestant nature but also of other material as well. With the Counter Reformation, Protestant books were confiscated. As, apart from The Bible, there was a lack of Catholic reading material that could serve as a substitute for the confiscated books, for a while, reading in general was frowned upon. This is again reflected in the wills made by the citizens, with bequeathed books not occurring in wills until the eighteenth century. Here the sole exception is the Deacon Lambert, who in 1628 confiscated 127 Protestant books, leaving 101 of them in to the arch-Catholic Capucine Order.

The other church that dominates the square is the Parish Church of Saint Vitus, otherwise known as „The Cathedral of the Wachau“. This was where the eleventh century Romanesque basilica stood. After falling into disrepair during the Renaissance, it was knocked down in 1616 in order to make way for a Counter Reformation, Baroque structure designed by the Italian architect, Cypriano Biasino. Where the Counter Reformation was sceptical about the advantages of a reading population and of independent critical thinking, it was in no doubt about the need for a language of visual art that was as manipulative and convincing as it was overwhelming and bombastic and all of this may be found inside.

Returning to the Obere Landstrasse, on the right-hand side, at number 10, an unassuming entrance leads into the Fellnerhof. Here there is another impressive example of an arcade built over two stories. Once a dance salon, this is where courses in further education are held and on the right, a stairway leads up to the course rooms. Here an ornate moulded ceiling may be seen whose imagery is continued in a larger room above. Although at first sight, this looks like a relief version of a grotesque painting, it is not but rather is an inversion of everything that grotesque painting stood for and tried to represent. With respect to painting, the term „grotesque“ refers to a style of decorative painting that derives from the grottos discovered during the Renaissance in Rome and Pompei. Re-interpreting the murals, Renaissance artists evolved a form of ornamentation that going beyond the strictly ornamental, is alive with interconnected elements, flowers for example, being linked with masks, whilst singing birds stand next to dolphins, all held together by filigrees of twirling, interconnected lines. From around 1485/1490 onwards, this style of decoration became highly fashionable and although over the decades, it became mannerised and lost its spark, two lively examples are preserved in Museum Krems. One is a panel of fresco that features interconnecting leaves and flowers, combined with an urn and ornamental, metallic objects.

The other is a masterpiece of marquetry that adorns a cupboard imported from Germany by Doctor Kappler and which in a bequest made in 1552, he explicitly left to the town. Where the two upper panels show ruins, the lower panels show interconnected masks, faces in profile, birds, dolphins and flowers.

The point of all this ornamentation is not the creation of a dearth of irrelevant, extraneous detail but rather is designed to evoke a shifting, dynamic world of metamorphosis and interpretation. During the Renaissance, the world was seen as a book which it was mankind’s task to decode. Here however, the correspondences that pertained between the macrocosm and the microcosm were seen as being so manifold that one interpretation did not necessarily exclude another, so that a multi-layered validity of meanings was possible. In this way, the world was seen as pulsating with ever-shifting meanings and interpretations, this being expressed in grotesques. In the moulded ceilings of the Fellnerhof however, this is not the case and something else has happened that is independent of the talent (or lack thereof) of the person who executed the reliefs. As argued by the historian, Robert Streibel, the combination of human faces with markedly large noses and pelicans carries a disturbing anti-Semitic message, in which there are no shifting meanings and no subtle meanderings. Although the Jews had been expelled from Krems a hundred years before and only a few Protestants still remained, in the Fellnerhof, a fiend has been found and demonised, so that Christian truths can be made to appear unquestionable. As the ceilings of the Fellnerhof were completed in 1619, there is good reason for giving this date as the end of the Renaissance in Krems and the beginning of a culture dominated by the Counter Reformation in which simplistic formulas and truisms were all-important and the real complexity of truth was negated and ignored. This stands in marked contrast to the wild man encountered above the apothecary at Untere Landstrasse 2, who with a variety of explanations as to his origins, challenges the viewer to explain his presence and why he should be adorning a house at such an prestigious intersection. Unlike the culture of the Counter Reformation, this puts the onus of interpretation on the viewer, ascribing and inviting individuals to form their own opinions and discuss their views in a culture of open debate.

A year later, the Corpus Hermeticum was identified by Isaac Casaubon as a collection of Neoplatonic texts that had been written by a number of different authors during the second century AD. Although the spiritual significance of the texts is unrelated to when and by whom they were written, as Renaissance Humanists had made much of the text’s supposed antiquity, the dating of the texts and the defusing of the idea that they had been written by a single person, served to debunk of their credibility and slowly the way was being paved for a new, more rigourously scientific view of the world.

Continuing on towards the Steiner Tor, a final example of an courtyard arcade may be found at Obere Landstrasse 32. Here rooms can be booked and in an atmospheric Renaissance courtyard, a meal enjoyed. As its name, „Alte Post“, says, this was once a post house and around the corner in the Schmidgasse, the original entranceway, half sunken by the rising level of the street, may still be seen. Continuing on along the Schmidgasse, brings one to the Körnermarkt. Here, twice a week, grain was sold and once a year, saffron, which for a few hundred years was produced in large quantities in the Wachau. On the other side of the square is the Dominican church, behind which lies the monastery complex and Museum Krems. Here the interwoven threads of the town’s complex history may be experienced in atmospheric and history-laden rooms where for centuries monks worked, ate and slept. The themes covered in the museum include, trade and commerce, the guilds, all aspects of wine-making, the lives of the town’s burgesses, the Roman presence, the Medieval ages and the Slav origins of Krems and Stein. A model of the town at the end of the eighteenth century, gives an overview of the town, with the raised plateau, churches and city walls all being easily identifiable. The heart of the museum is a cloistered courtyard, three sides of which are Baroque and one side of which has been restored back to its original Gothic appearance. In the cloister, a superb collection of Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque sculptures is housed including the Baroque sculpture of the Virgin Mary that originally stood atop the column that overlooks the Körnermarkt.